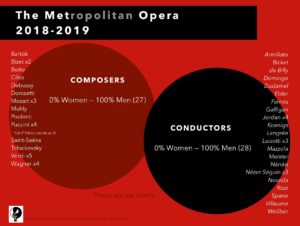

Over the week, there have been waves of backlash at The Metropolitan Opera’s newest season announcement. A recent Washington Post made the rounds, taking to task the institution’s insistence on an entirely white and male composer list, as well as a completely male roster of conductors taking the podium.

Chicago is especially no exception, as evidenced by the Lyric Opera’s lack of awareness in their recent copy for their 2018/2019 season right on their website:

“We pride ourselves on bringing you diverse programming, and the 2018/19 Season is no exception. Verdi and Puccini in all their passion, elegant Handel and Mozart, romantic Massenet, mighty Strauss and Wagner—there’s no end to the riches that will make this season one to remember.”

As a white man, there have been and continue to be countless times in which I have needed to recognize that privilege, white supremacy, homophobia, toxic masculinity, and gender normativity are layered issues. It’s easy to call a Nazi a racist because they are so obviously a racist. Not all racists are willing to take up that mantle.

Recognizing that Classical Music has implied White Supremacy for centuries is hard for those that study the art form. In fact, that correlating The Met’s continued programming of dead white men to the rise of White Supremacist tendencies in America is not a far stretch is starting to become apparent to those that follow and review the company’s season announcements.

Of course Italian Opera traditions are rich and are the backbone for many composers, but when an American institution, founded on the grounds of Natives and whose nation’s economy was fueled by the labor of slavery continues in 2018 to program exclusively white men, there’s a message being sent to those who don’t fall into that category.

“You need to prove yourself extraordinary, so work harder and watch your step.”

It’s a Privilege to be able to Critique without Professional Fears

I didn’t want to write this editorial. As a person with privilege, it feels like an echo chamber of bad takes and dysphoric triggers. But as an editor, I reached out to countless folks, who will here remain nameless, that have said ‘thanks for the consideration, but I don’t think my career can carry this burden.’

I’ve made a habit of picking fights on facebook threads in classical music groups. If you’re friends with me, this isn’t news to you. And I’ve gotten backlash for that. But for every person I’ve called out, or had call me “rude” or otherwise attack my character, I’ve had folks reach out to me to thank me for saying something.

I’m not writing this now to pat myself on the back, I’m just trying to figure out a way to have on the record the opinions and societal pains of those who are too young or committed to their career to make sure they’re not being dealt with through oppression.

For the case of the Met, a young female composer can’t make their case without fear of name recognition. Classical Music’s seemingly almost precognitive ability to classify composers and performers solely by their gender is well documented, like when in the 1970s and 1980s, most symphony orchestras in the United States began adopting “blind” auditions whereby the identity of potential candidates was concealed from the jury by a screen.

The findings were clear. “Blind” auditions increased the likelihood of female musicians being selected by 30%. According to analysis using roster data, the transition to blind auditions from 1970 to the 1990s can explain 30 percent of the increase in the proportion female among new hires and possibly 25 percent of the increase in the percentage female in the orchestras.

Opera Composer’s Whiteness Has Stood in the Art Form’s Ways for Centuries

In the work Blackness in Opera, edited by Naomi André, a series of black scholars take to task a series of historical placements that have helped to create the space in which we find the art form today. In André’s own chapter, “From Otello to Porgy, Blackness, Masculinity, and Morality in Opera,” she points out where even Classical Music’s best intentions can go horribly wrong.

In the work Blackness in Opera, edited by Naomi André, a series of black scholars take to task a series of historical placements that have helped to create the space in which we find the art form today. In André’s own chapter, “From Otello to Porgy, Blackness, Masculinity, and Morality in Opera,” she points out where even Classical Music’s best intentions can go horribly wrong.

Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue, a work heavily influenced by the jazz movement, was the first representation that the art form had with orchestral audiences, but at the time it was clear that its warm welcome was thanks to Gershwin’s whiteness. Gershwin then followed this work up with Porgy and Bess’ predecessor, Blue Monday. This work was panned heavily by the black community of the time, and André documents this extensively.

“In five days and five nights, De Sylve and Gershwin managed to turn out something unique- a one-act vaudeville opera they titled Blue Monday. For orchestrations, Gerhwin turned to a black musician friend, Will Vodery. Among those impressed with the opera during rehearsals was Pail Whiteman, the enthusiast of the new jazz idiom and an admirer of the way Gershwin evoked a Harlem mood through his use of jazz themes. While hailed at its tryout in New Haven- the occasion was so momentous for George that he dated his nervous stomach from that moment- the piece was barely noticed in New York. One reviewer, though, delivered it a smart slap. ‘The most dismal, stupid and incredible blackface sketch that has ever been perpetrated. In it a dusky soprano finally killing her gambling man. She should have shot all her associates the moment they appeared and then turned the pistol on herself.’”

To be frank, Blue Monday was a minstrel show. The work Gershwin did before he wrote Porgy and Bess was appropriating black idioms through blackface.

“The crudity of this little opera was compounded by the white actors playing and singing in blackface. Only two of the songs- “Blue Monday Blues” and “Has Anyone Seen Joe?” – stood out. George White decided that the opera’s bathetic plot ran counter to what audiences expected from a lighthearted revue and excised it from the production after opening night.”

This climate set the stage for Porgy and Bess to be the work that it was, but when we talk about the work’s history we don’t talk about how poorly it was received by actual black people. For black critics, it depicted a stereotyped black experience and brought white attitudes to a black story.

It was Duke Ellington himself who said that “The times are here to debunk Gershwin’s lampblack negroisms. The music does not hitch with the mood and spirit of the story. It does not use the Negro musical idiom.”

Ralph Matthers, music critic for The Afro-American, agreed that ‘it most certainly isn’t Negro.’ The music, he said, had none of “the deep-sonorous incantations so frequently identified with racial offerings. The singing, even down to the choral and the ensemble numbers, has a conservatory twang. Superimposed on the shoddiness of Catfish Row the seem miscast.”

Circling back to the Metropolitan Opera’s upcoming season, the company will continue its production of Otello, with white tenor Stuart Skelton singing the title role, which for those not familiar, is a black character whose race is central to the plot.

Of course, this isn’t new for the Opera. For Verdi and Boito, that the main character was black was a joke Boito used to get Verdi out of retirement.

Again, from Blackness in Opera:

“Even more striking by today’s standards, several times in the correspondence between Verdi and those who were involved in the creation of Otello are references to getting the “chocolate” ready; Giulio Ricordi even sent Verdi a holiday panettone (a traditional Milanese cake) around Christmas in 1881 and 1992, each topped with an unfinished figure of Otello in chocolate – not-so-subtle indications that he was looking forward to Verdi’s completed opera.”

Where are White Folks and Why are they Not Qualifying and Actively Dismantling White Supremacy

I quote Blackness in Opera here so heavily because it is not a new book. Compiled in 2012, the Met’s continued practices is evidence that although it can seem like consulting with a black person at all would be a simple task, White organizations are incapable of doing that in fear of confronting perceived standards that classical music imposes.

In fact, The Met goes out of its way to celebrate its season. In the Washington Post article mentioned above, writer Anne Midgette notes that “The Metropolitan Opera’s announcement on Thursday capped a whole chain of seasons heavy on standard classics, like pantries laden with white bread, touting the appearance of a single piece of olive focaccia as if it demonstrated a commitment to range and variety.”

That’s the problem. Classical Music is so Eurocentric that it sees Eastern European programming (or, GASP, Russians) as a commitment to diversity. It doesn’t recognize that promoting the works of the diverse people in its own country is what 2018 is actually craving.

Until Classical Music is able to take a long, hard, look in the mirror at what having absolutely male voices in the field as composers and conductors, it will always lag behind what’s happening artistically.

We constantly ask what the art form can do to tackle that its audience is literally dying, while otherwise not acknowledging that most A-level houses have been using practically identical Boheme productions for the majority of its seasons.

Opera will always, and I personally think should always have some callbacks to its traditional roots. I am definitely not calling for the striking of the record of Puccini, Verdi, or Rossini. I am calling for- even just a little- consideration. An outreach program that actively trains women, trans, gender non-comforming, and POC folks. Programming more than one new Opera. Lowering the “production value” bar a smidge to make room for actual current day artmaking.

Opera seems to be founded on telling the stories of the underdog, of the oppressed, of the underprivileged. How then, can we expect to give those stories their deserved consideration if we don’t even invite them to the table?

Very interesting article! I agree with most of the author’s points. Here are a couple of observations that seem important.

“Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue, a work heavily influenced by the jazz movement, was the first representation that the art form had, but at the time it was clear that its warm welcome was thanks to Gershwin’s whiteness.”

Presumably what the author meant to say was that this was the first representation the art form of jazz had *within the context of classical music.* Jazz had been representing itself very successfully for over a decade by the time Rhapsody in Blue came out, and at that time had a vastly broader appeal and outreach than classical music would ever again achieve.

“Until Classical Music is able to take a long, hard, look in the mirror at what having absolutely male voices in the field as composers and conductors, it will always lag behind what’s happening artistically.”

At what time since the early twentieth century has classical music NOT lagged behind what’s happening artistically? I am a great lover of classical music, but I will never make the mistake of viewing it as contemporary. Which is liable to attract more attention from music lovers and media: a performance of Verdi’s Otello or Beyoncé headlining at Coachella? It’s telling that the author of this article is lamenting the whiteness of opera at a time when Hamilton has outperformed practically every musical ever released.

Classical music and opera have been left behind and replaced by more contemporary art forms that speak to today’s more diverse audiences. It’s certainly useful to point out the lack of forward thinking that has been classical music’s downfall, but it would be a mistake to forget to celebrate the culturally rich art which has come along to take its place.

Can a white person even critique whiteness? Perhaps even this article is perpetuating the problems addressed in this piece.

Ya. Sure. Why not? .

Someone should ask Eric Owens about this.

I’m really glad you wrote this and actually I think it needed to be written by a person who self-identifies as having privilege and (superficial) things in common with the people who are the gatekeepers of programming–so, thank you. I’ve shared this with a lot of friends who are in classical music, and based on our conversations, I suggest that the solution is not training for the women, trans, GNC, POC folks who are already doing the artmaking as composers and performers. As a friend said: non-inclusive programming is a gatekeeper problem. It’s not that the work doesn’t exist (or that producing it would involve lowering the production bar, which, yuck. Ask last year’s Pulitzer winner whether she thinks that’s necessary). Probably the current gatekeepers just need to go, but barring that, massive training initiatives for *them*, please.

Agree 100%, and would have made this, “Opera seems to be founded on telling the stories of the underdog, of the oppressed, of the underprivileged. How then, can we expect to give those stories their deserved consideration if we don’t even invite them to the table?” the opening salvo, not the closing bell.

[…] series of essays could be written about racism within the classical music community. Here's an excellent opinion piece by Daniel Johnson earlier this year about this subject and sexism in the classical music arts […]