Pictured above: Christopher Sylvie, Karen Fort, Zoë Pike and Lyle Mays in Last Days of the Commune by Bertolt Brecht, performed in 2017 at Prop Thtr/Photo: Provided by Prop Thtr

Editor’s Note: This is the second installment of Makers and Breakers, Scapi Magazine’s monthly column about the history of experimental history in Chicago by our DIY theater and performance contributor Felix Abidor.

“We work with being,

But nonbeing is what we use.”

—The Tao te Ching

A fun exercise to kill some time: find every experimental theater company currently operating in Chicago. The process might take the better part of the afternoon. A fun exercise to kill even more time: find every experimental theater company that has ever operated in Chicago. The number increases exponentially. Chicago has long been an incubator for new companies producing new works. Every crop of recent graduates from universities is reliable for at least a few. With almost perfect regularity one of two things happens to each company: it becomes really big (e.g. Steppenwolf), or it fizzles. Perhaps one company has formed the notable exception—The Prop Thtr. Currently operating out of a two-venue space in Avondale, The Prop Thtr has existed for 37 years. The company has rarely thrived financially. Yet, it has endured, and in its endurance has produced or incubated some of the most vital work in the Chicago theater community. How it formed, survived and evolved are questions that form a useful support in understanding the Chicago theater-organism.

The Early Years

In a curious twist of theater history, many of the most experimental companies develop during times of social and political conservatism. In this way, The Prop Thtr is par for the course.

Transport back in time to 1981: the counterculture experiments of the 1960s had foundered upon the rocks of Vietnam and Watergate. In a repudiation of the Civil Rights era, Neoconservatism ascended, bringing such cultural mainstays as Phyllis Schafly (famous for her anti-feminism), Newt Gingrich (famous for his anti-working government), and—of course—Ronald Reagan. One can say much about Ronald Reagan and his effect on the arts. While one can make the argument that Ronald Reagan stymied significant portions of the progressive wave 75 years in the making, his effect on the arts is less clear. Though Reagan is portrayed as the great nemesis of the NEA, that organization actually emerged from the Reagan era with a higher budget than it had when it started. However, the tide of social conservatism that Reagan espoused undoubtedly despaired of the populist art most associated with postmodernism. In this way, The Prop Thtr emerged as a counterweight to the forces moving the arts toward elitism.

Like many of its experimental predecessors—and successors—the founders of The Prop Thtr met in college. Scott Vehill and Stefan Brün both studied at Columbia College. Vehill was pre-law, and Brün—a grandson of a prominent actor and director of German theater and film—was studying in the Arts, Entertainment and Media Management Program. They collaborated first on an adaptation of 1984. Vehill directed and Brün performed. Following that, they followed Brün’s heritage into a theatrical style that would reverberate throughout The Prop Thtr’s history—Brechtian Theater. Brün forged a new translation of Puntila and Matti, his Hired Man staged a production, with Vehill performing. After this first production, they resolved to remount it outside the confines of the college. They rented a storefront—formerly used as a strip club—in East Lakeview. With that, a storefront theater was formed.

At this point, one must be made aware of the stylistic revolution inherent in producing Brechtian theater. Particularly in the early 1980s, the objects of alienation—Brün gestures to the visible stage lights—were less prominent than they were now. At the time of The Prop Thtr’s founding, most of the city’s theater spaces, even the storefronts, were producing traditional stage plays. The Prop Thtr cut further across the grain by specializing in mostly in his lesser known works. Though Brecht’s themes of class struggle and social alienation reverberated across the works the company produced in later generations, the churn of the theater company’s growth soon altered its focus.

If one were to point to a consistency among The Prop Thtr’s history, it would be turnover. Most of the founding members of the company do not work there anymore. Many of the major luminaries in its history don’t even work in theater anymore. It is therefore characteristic that, not long after the company’s creation, founding member Stefan Brun left. He moved to Germany to study with experimental theater companies and did not return to The Prop Thtr for over a decade. Shortly thereafter, the company moved to a new venue in Lincoln Park. Concurrently, new members joined the company. Among them were Tara Riley, Karen Forsberg and Gray Giuntoli.

With the change in personnel came an alteration in the company’s mission. No longer was Brecht the focus. In fact, the aesthetic focus became less significant: though the new three chief collaborators—Vehill, Forsberg and Giuntoli—shared an interest in producing new work, the work they wanted to produce was significantly different. If one were to characterize the aesthetic of this time, it was work from the Beat Generation. However, little else was there to combine them, so they split the production schedule up. Each of the three got a four-month production schedule to work with as they saw fit. They could choose to sell it to someone else, but each of the three was responsible for a third of the rent. The focus of the company, therefore, shifted toward the development of new work.

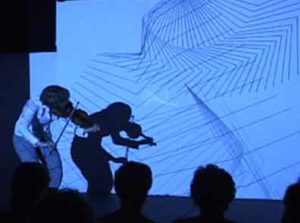

Reardon in Last Days of the Commune by Bertolt Brecht, performed in 2017 at Prop Thtr/Photo: Provided by Prop Thtr

The ensuing period of The Prop Thtr, stretching from the late 80s to the late 90s, saw the rise of the theater is a non-equity force in the Chicago Fringe. Forsberg’s play Mass Murder sold out for several months, won critical acclaim and even raked in Jeff Nominations for several of its cast members. The Prop Thtr’s 1994 production of Paul Peditto’s Never Come Morning retains the record for the most amount of non-equity Jeff Award Citations ever given to a single production with nine. To this day, The Prop Thtr remains the most critically acclaimed non-equity theater in the city.

As the company was experiencing artistic success, it retained the existential raggedness typical of a fringe theater. In whichever space they occupied, they rented rooms and even hallways to poor artists. They moved once more—this time to Bucktown/Wicker Park—before being priced out of their venue and thrown into itinerancy. They remained without a physical location from 1994 through 2003. The financial contributions of one of its members—Jonathan Lavan’s parents had a healthy endowment—kept the lights on. Still, the company continued to live a meager existence for much of the 90s and early 2000s. Lavan has since left the fringe scene and now has a family in the suburbs.

The sustained success of The Prop Thtr, in spite of the financial concerns customary of a fringe theater, eventually attracted both the attention of its new and old collaborators. The sustained quality of the new work being produced attracted the attention of David Goldman, special programs director at the Eugene O’Neill Theater Center, a prominent new-play incubator. Goldman and the staff at The Prop Thtr collaborated to form a new play festival in Chicago in 1998. The festival formed a kernel that expanded to other theaters across the country that were dedicated to producing new work. The theaters organized to form the National New Play Network, an organization designed to “develop, produce and extend the life of new plays.” The Prop Thtr remains a core member in the organization, the smallest theater in the group.

The organization and festivals served to lure Brün back from Germany for good. Previously, he had only returned to direct individual productions. He took over as artistic director of the company, just as The Prop Thtr was making a final step toward consistency—a permanent home. Creating an S-Corporation, The Prop Thtr moved into its final location on Elston Avenue. The new space has two performance/theater spaces. The original strategy was to partner with a collection of other theater companies, who paid rent to use the space when The Prop Thtr was not actively producing a show. The arrangement created a duality in identities for The Prop Thtr. The organization became both a producing theater company and a cheap venue for other companies producing new and experimental works. In this way, The Prop Thtr became the parent of other theaters working to produce their own work.

The New Blood

Mirroring The Prop Thtr’s history of foundation in the midst of social and economic unrest, the current crop of Prop leadership can be traced to another time of economic hardship. After graduating from college in 2012, Olivia Lilley entered the professional world at a time when the welcoming committee was a destructive maw. The housing market crashed in 2008, and four years of slow recovery had devastated the professional and artistic world. Theater companies shuttered all over the country and the mundane jobs that formed the bedrock of any theater artist’s economic security—the marketers, servers and bartenders—were scarce.

Facing the difficult odds, one has a tendency to gravitate toward either a victim or survivor mindset. The difference is in the power and responsibility one takes: the victim renounces responsibility and laments their lack of power. The survivor moves forward toward self-sufficiency and toward thriving. In times of hardship in the central zeitgeist, survivors head toward the fringe. Lilley was a paragon for this movement. Posting an ad on an audition website, she cast a group of people and produced her own work. Having 300 dollars to her name, she borrowed 1000 dollars from a relative and made the whole sum back. Next, she rented her own DIY space and developed it as a location for other theater companies to rent. In this way, Olivia Lilley’s response to her environment mirrors that of The Prop Thtr.

It is therefore unsurprising that the paths of Lilley and The Prop Thtr would cross. While scouting locations for a mobile production of Wolfgang Goethe’s Faust, Lilley met Brün, who suggested she perform it in the loft above the theater. The mendicant performance embodied the ethos that characterized The Prop Thtr for the preceding 37 years. In early 2018, Brün offered Lilley the title of Artistic Director. Her first season is composed entirely of ensemble projects devised in house. The theater dedicated to providing a space for new works has therefore made the final evolution into incubating new works of its own.

Lilley’s vision of The Prop Thtr retains much of the ethos that set The Prop Thtr apart throughout its history. In a theater community ever-obsessed with resumes, Lilley envisions The Prop Thtr in a way that emphasizes the rough and the risky. Instead of plays written and performed by established directors, Lilley proposes seeking out directors and playwrights who have been with the play and the beginning. In short, she seeks plays grounded from and for the teeming masses of the Chicago community.

“This is just our duty as citizens to find the good shit,” Lilley remarked.

It is important to note that, for The Prop Thtr, the philosophy is not revolutionary, but rather a sublimation of the philosophy that has driven the theater for its entire existence.

Yet, to see The Prop Thtr today is to see a theater with its feet in both the past and the present. A new generation has adopted the venerable producing house. Yet, the vestiges of the old remain. Brün stays on as the venue’s manager. Many of the original members and patrons come to shows and engage with younger people. Unlike the crowds that go to a Steppenwolf show, however, the expectation is not necessarily to see a polished work. The space creates a rare opportunity for Baby Boomers and Millennials—two of the most maligned generations—to meet and discuss. This contrast is partially by design. Lilley envisions a space where people of different aesthetics can come, discuss, and battle. Yet, the dichotomy is in many ways the inevitable product of that rarity that The Prop Thtr possesses, the home of theatrical lost boys that never grew up.[1]

Ultimately, if one were to search for a reason for The Prop Thtr’s continued existence, one would be forced to the conclusion that The Prop Thtr barely exists at all. Throughout its 37 year history, there has been little thread that ties the original theater to its present iteration. Those that started the company came and went. The original building was replaced with a new one, and another new one, and another. Even the aesthetic vision has evolved well beyond its origins.

However, that would be a false estimation. The theater exists in its artists—ever-rotating—ever moving to bigger things or nowhere at all. It is in itself a devised work; it exists by and for the story of its characters.[2]

Tune in next month for another Chicago experimental history column by our DIY theater and performance contributor Felix Abidor.

[1] Prop Thtr is currently producing an adaption of Peter Pan, entitled Neverland.

[2] This article was based in part on interviews with Stefan Brün and Olivia Lilley. Special thanks to Kerri Reid for her in-depth research on the theater’s history.

A great article about a great theater. However there is some inaccurate information. I was the Managing Director and then Executive Director from 1990 to 2005. And while my parents made donations they did not “make a heathy endowment”. Rather, my gift to Prop was my ability to get the company organized. To give the company a professional look, form a board of directors, get grants (including an NEA) and take the company to the next level. I am also fairly certain that the play “The Kentucky Cycle” produced some years after “Never Come Morning” received more non-equity citations. I believe thirteen. Lastly, I do not “have a family in suburbs”. I live in San Diego where I am a nature photographer/environmentalist and own a organic pet food store with my wife. In future a bit of fact checking would be great.

Jonathan Lavan

Managing/Executive Director

Prop Thtr Group

1990- 2005

One should also mention that Prop member Charles Pike who received a Jeff Citation for his acting work in Mass Murder in the early 90’s is the father of current Prop Thtr member Zoe Pike. Zoe like here father is a true talent who is making her mark in the independent film industry.