Marian Anderson’s groundbreaking performance at Lincoln Center and her historic debut at the Metropolitan Opera opened doors for other black opera singers in the U.S. to break onto the scene, and spurred a movement. Superstars such as Leontyne Price, Grace Bumbry, Shriley Verrett, Martina Arroyo, Simon Estes, and Jessye Norman had great careers, but still faced many odds.

Looking at the struggles that these great talents faced brings to the attention many issues in opera. How do our visual expectations of certain characters affect our perception of their performances? Do race specific roles have to be cast by people of those ethnicities, and if they’re not, does it take away from the drama? What real opportunities did black American opera singers have back then to be taken seriously, and how did Gershwin’s Porgy & Bess play a role in that?

The first singer that followed Marian Anderson with international fame, and perhaps one of the most influential black opera singers of all time whose inclusion here is a must, is Leontyne Price. Born Mary Violet Leontyne Price on February 10, 1927 in Laurel, Mississippi, Leontyne faced much adversity on her climb to the mountaintop. Though her voice was praised for its vibrant and soaring tone, many critics still had trouble seeing her in “non black” roles.

When a ‘great diva’ (who remains unnamed) was asked in the 1960s if she’d heard Leontyne Price, she remarked,

“Ah yes. Price. A lovely voice. But the poor thing is singing the wrong repertory!” When asked what Price should be singing, she replied, “Bess. Just Bess.”

Unfortunately this view at the time was not uncommon. A music critic by the name of B.H. Haggin wrote in a review in the 70s,

“Price presented with her Donna Anna the same obtrusive incongruity as previously with her Leonora in Il Trovatore and her Pamina in The Magic Flute, but not with her Aida: When I look at what is happening on a stage, my imagination still cannot accommodate itself to a black in the role of a white.”

Despite the critics and the prejudices of the time, Leontyne still acquired international success and had a long, lucrative opera career. Time magazine called her voice

“Rich, supple and shining, it was in its prime capable of effortlessly soaring from a smoky mezzo to the pure soprano gold of a perfectly spun high C.”

She is classified as a lyric spinto soprano, or a “pushed lyric,” and was especially well suited for roles of Verdi and Puccini. Some of Leontyne’s most famous roles include Verdi’s Aida, Cio-Cio san in Puccini’s Madama Butterfly, Bess in Gershwin’s Porgy & Bess, Puccini’s Tosca, and numerous others. In 1964, Leontyne received the Presidential Medal of Freedom. She has also received the Kennedy Center Honors, The National Medal of Arts, and 13 grammy awards.

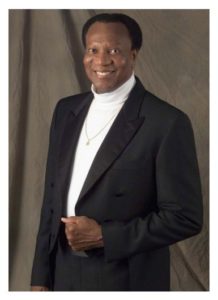

Someone who was close friends with Leontyne Price and had a magnificent international career was Simon Estes, a bass-baritone. Estes had a tougher time though, than Price, being a man in addition to being black. Simon was born on March 2, 1938 in Centerville, Iowa. His grandfather was a slave who was sold at auction for $500, so Simon was always very aware of the racial issues in this country. He began his career in Germany and achieved great success in Europe playing mainly roles of Verdi and Wagner.

He was the first black male to sing a leading role at Bayreuth (The Flying Dutchman), which is historically quite racist, and performed there for the next six years. It was harder for Estes to break into the American opera scene, but he finally made his American operatic debut at the Lyric opera of Chicago in 1971 with a very minor role. He went on to perform at several other companies in the U.S., but was ignored by the Metropolitan Opera until 1981 when they finally offered him a contract. He was warned by Leontyne, “Simon, it’s going to be even more difficult for you. Because you are a black male, the discrimination will be greater. You have a beautiful voice; you are musical, intelligent, independent and handsome. With all of these ingredients, you are a threat. It will be more difficult for you than it was for me.” Audiences responded well to his debut as Hermann in Wagner’s Tannhauser.

He was the first black male to sing a leading role at Bayreuth (The Flying Dutchman), which is historically quite racist, and performed there for the next six years. It was harder for Estes to break into the American opera scene, but he finally made his American operatic debut at the Lyric opera of Chicago in 1971 with a very minor role. He went on to perform at several other companies in the U.S., but was ignored by the Metropolitan Opera until 1981 when they finally offered him a contract. He was warned by Leontyne, “Simon, it’s going to be even more difficult for you. Because you are a black male, the discrimination will be greater. You have a beautiful voice; you are musical, intelligent, independent and handsome. With all of these ingredients, you are a threat. It will be more difficult for you than it was for me.” Audiences responded well to his debut as Hermann in Wagner’s Tannhauser.

Grace Bumbry (born January 4, 1937) is considered one of the best mezzo sopranos of our time. She had a wide range and was also a successful soprano for many years. She began her career in Europe, like many black opera singers tried to do, because there wasn’t as much racial tension and discrimination as there was in the U.S. at the time. She reluctantly played the role of Bess in the Metropolitan Opera’s production of Gershwin’s Porgy & Bess. Although Grace was very successful, she carried a reputation of controversy for playing both soprano and mezzo-soprano roles, and apparently for being difficult to work with. About her struggles of being a black artist during a time of heavy racial tension, Bumbry said:

“That is very private to me, and I have spent my life going back and forth about it. And some people said, ‘Oh, she’s black and pushy – that’s why they’re hiring her.’ And others said, ‘Oh, she’s black – let’s not hire her.’ And when I sang Schubert and Liszt and Brahms…they said, ‘Sing spirituals, don’t be so pretentious.’ And when I sang spirituals and tried to do it in a way that wasn’t slick, they said, ‘That’s all she can do, and she’s crude! A real artist sings Brahms and Liszt!’”

Other black opera stars in the first generation after Marian Anderson were Martina Arroyo (born 1937), a soprano with a great international career; and Shirley Verrett (1931-2010), a mezzo-soprano who successfully transitioned to soprano repertoire and enjoyed great fame from the 1960s to the 1990s.

One singer that is of the following generation that I feel is very important to discuss is Jessye Norman (born 1945). Jessye is a critically acclaimed operatic dramatic soprano (though she sometimes sang traditionally mezzo-soprano roles), and recitalist. Jessye was known for her rich vocals, her Wagnerian roles, her great size, and her infectious spirit. She is perhaps one of the only black opera singers that has acquired mainstream success and is known by those that are not as familiar with the operatic art form. Her spirituals have helped her bridge the gap between “popular” music and classical repertoire. Jessye has received many prestigious honors and several Grammy awards.

One singer that is of the following generation that I feel is very important to discuss is Jessye Norman (born 1945). Jessye is a critically acclaimed operatic dramatic soprano (though she sometimes sang traditionally mezzo-soprano roles), and recitalist. Jessye was known for her rich vocals, her Wagnerian roles, her great size, and her infectious spirit. She is perhaps one of the only black opera singers that has acquired mainstream success and is known by those that are not as familiar with the operatic art form. Her spirituals have helped her bridge the gap between “popular” music and classical repertoire. Jessye has received many prestigious honors and several Grammy awards.

With all of these great singers breaking so much ground in the 20th century, it’s hard to imagine why race might still be a factor in the casting of operatic roles. Of course, there are still racist directors and people in positions of power that have a hard time seeing past color, but there is also a more complex dynamic that comes into play.

Race is embedded so deeply in American culture and society, and we have such long-standing traditions of “white” being the social norm, that there are complex subconscious expectations we have when going to the opera. We expect to see white people as the leads, because that’s the way it’s been for so many years. Additionally, we have certain roles that are race specific, and as one of Leontyne’s critics said, sometimes the imagination cannot fathom someone of another race playing those roles. Perhaps it takes away from the drama for some audiences when the casting is not “authentic.”

For example, how do people take it when there is a person of color playing Cio-Cio San, a character who’s Japanese heritage is a major plot point in Madama Butterfly? Is it strange to see Ethiopian princess Aida played as a white woman who is clearly not Ethiopan? And how would people react if there was a staged production of Porgy & Bess in which Bess was played by Renee Fleming? These are questions that continue to come up and are the topic of much debate in the past and current opera world.

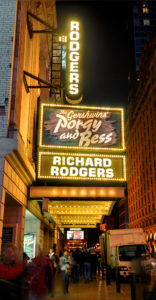

On the subject of Gershwin’s Porgy & Bess, there is also much controversy. As the main representation of blacks in our very white world of opera, it enables both opportunity and detriment. Although the opera has historically helped many black opera singers begin their careers, and even some make their whole careers, there is a danger here. Though the music is generally regarded as great, the storyline is considered by many to be stereotypical and offensive. Not only does it perpetuate the negative stereotype that has been placed on the black community over the years, it causes many singers to get ‘trapped’ and typecast. This is dangerous, and perhaps allows the operatic community to continue keeping black opera singers in a box, and keep them satisfied so they won’t feel the need to ‘infiltrate’ the historically white canonic roles.

On the subject of Gershwin’s Porgy & Bess, there is also much controversy. As the main representation of blacks in our very white world of opera, it enables both opportunity and detriment. Although the opera has historically helped many black opera singers begin their careers, and even some make their whole careers, there is a danger here. Though the music is generally regarded as great, the storyline is considered by many to be stereotypical and offensive. Not only does it perpetuate the negative stereotype that has been placed on the black community over the years, it causes many singers to get ‘trapped’ and typecast. This is dangerous, and perhaps allows the operatic community to continue keeping black opera singers in a box, and keep them satisfied so they won’t feel the need to ‘infiltrate’ the historically white canonic roles.

It could be very beneficial to the opera community to consider other black operas as well. There are several operas that are just not done. There is a popular belief that if a show, movie, play, or opera doesn’t root its focus in the point of view of a central white character, it will fail to be lucrative. I don’t think this is true, and shifting demographics of our country might prove the contrary. Operas such as Anthony Davis’ Amistad and X, The Life and Times of Malcolm X, as well as Scott Joplin’s Treemonisha and William Grant Still’s Troubled Island could breathe new life into the opera community if given the chance. Performing such works could change the audiences paying for tickets, as well as the public’s perception of blacks and their role in opera.

Many companies have emerged as a result of racism in opera, to provide education, enlightenment, and opportunities to the black opera community. Opera Ebony, the longest surviving African-American opera company in American history, was founded in 1973. They perform many of the operas in the standard repertory, as well as some of the lesser known black operas. There is also Houston Ebony Opera Guild (1992), Harlem Opera Theater (2001), and our very own South Shore Opera Company of Chicago (2008) which is a non-profit company that puts on concerts as well as staged works.

So where is opera headed? I believe that along with the “browning of America” bringing a new face to America, it will also bring a new face to opera. We are already starting to see it happen. Much progress has been made with regard to racism and racial tension in this country in all areas of media and performing arts. We are headed in the right direction, towards a “new normal,” and perhaps one day this will not be such a hot-button topic of discussion.

Be First to Comment