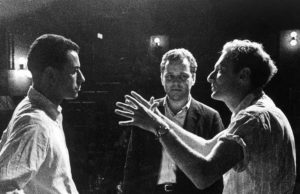

Pictured above: Original cast members of The Second City outside their Old Town performance space/Photo: The Second City

Editor’s Note: Scapi Magazine is launching Makers and Breakers, a new, monthly column about the history of experimental history in Chicago by our DIY theater and performance contributor Felix Abidor. This is the first installment.

When one brings up the premier cities to produce and see theater, the usual suspects tend to emerge: New York, London, Los Angeles, Berlin. Stuck at the back of the throat is always Chicago.

Billed as the Third Coast, Chicago has always shimmered just beneath the surface as a place to produce and see great work. In that mild obscurity lies its strength. In the absence of big-name producers and cynical actors, Chicago offers the opportunity to produce work that is high-quality, honest, and above all, cheap. Heeding the call of this unheralded harbor, hundreds of companies and thousands of artists have created and grown here. This essay series will be about those theater companies. Some have grown to become the Steppenwolves and Looking Glasses. Many, with their might and money expended, have relaxed into defunctitude. Each has left a mark, large or small, returning a favor to the city that shelters and nurtures them

We will begin this series in a surprising place: the Improv Company, the Second City. With a reputation as a breeding ground for wildly famous comedy talent, and a visitor log encompassing everyone from Chinese tourists to your uncle from Des Moines with the unintentionally spot-on John Belushi impression, few would consider the modern Second City to be an underground theater company. However, the early growth of Second City — from borrowed spaces at the University of Chicago and above dry-cleaners and Chinese restaurants — formed the prototype and precedent for many of the companies that followed. In exploring the roots of Second City, we are exploring the roots of the storefront scene in Chicago.

Before talking about The Second City, it would behoove us to learn about the Chicago during the time in which the company emerged.

Throughout the second half of the 19th Century, Chicagoans developed a pride in their city bordering on hubris. After the completion of the Trans-Continental Railroad, 19th Century Chicago underwent a massive influx of population and wealth. Between 1840 and 1850, the city grew from a settlement of 4400 to a city of nearly 30000, a growth of about 580%. Fueled by economic expansion and endless waves of immigration, the city continued to at least double in size every ten years until the turn of the century. The speed of the city’s expansion from provincial backwater to the “Hog Butchering Capital of the World” led many residents to conclude that, before long, Chicago would eclipse even New York as the premier economic and cultural destination in North America.

By the middle of the 20th century, however, the city’s expansion had run low on steam. After reaching a zenith in the 1950s, the population stagnated and even began to decline. Though the city was thriving economically, its economic clout failed to turn into cultural clout. Though the city was populous, most of its population lived in disconnected, sprawling neighborhoods. There, performance more closely resembled Old West saloons, with unskilled dilettantish performers providing mostly subpar performances for dinner guests. Though there was a professional arts scene, it was small and contrived. Most Equity theaters were confined to the Loop, where they hosted touring productions and Broadway reruns. Such an arrangement rendered Chicago subservient to the cultural waves of its coastal counterparts. The cultural servitude did not go unnoticed on the East Coast; in a series of essays for the New Yorker, writer AJ Liebling labeled Chicago, to the chagrin of its residents, “The Second City.”

Though Chicago’s sprawl preempted the development of a unique local alternative to Broadway, that very sprawl sparked the development of the theatrical forms we regard as quintessentially Chicagoan. Improv was chief among them.

To be clear, improv was not new. It had been practiced in varying forms since at least the 1600s, in the form of Commedia dell’Arte performers and clowns. However, the 1930s saw its maturation into a unique standalone art form. Much of that development happened in Edgewater, under the eye of Viola Spolin.

Spolin was not a traditional theater maker: though she studied theater at DePaul University and the Goodman Theatre and worked with New York’s Group Theatre while the company had its heyday, she was best known for her work as an educator. For several decades, Spolin taught recent immigrants and their children creative dramatics. Her students often could not speak English fluently, so Spolin developed a series of games to assist in communication. It was these immigrants who took suggestions and improvised before live audiences.

Spolin staged the first improv revue in 1939. The performance brought together actors from different cultures, languages, races and genders. Though few saw it, Chicago Daily News reviewer Howard Vincent O’Brien valued it at “about a dozen Broadway successes rolled into one.” While Spolin eventually wrote the “bible” of improvisational games, Improvisation for the Theater, her most valuable contribution in the history of Chicago might be the effect she had on her son, Paul Sills.

If one were feeling generous to Hyde Park, one might label The Second City as the brain-child of the University of Chicago. The university has been celebrated for its alumni and discovers— hosting the first instance of nuclear fission[1], renowned authors, sociologists, philosophers, politicians, mathematicians, etc.—and, in addition, many of The Second City founders were alumni. One is less inclined to toss the bone, however, with the understanding that, at the time those students were developing their work, the university had no official theater program. Seventy years later, it still does not have an official theater program. Instead, the students balance heavy course loads with student-run theater organizations.

Among them, Spolin’s son Paul Sills joined, and eventually led, the University Theater. There, he explored the experimental luminaries of his time–Brecht, Rimbaud, Beckett, Genet, Pinter. Sills arguably became a revolutionary in his own right, rebelling against the Stanislavskian Fourth Wall–anathema for his time. What set Sills’s work apart from many of his experimental peers was his work’s quality. His production of Brecht’s Caucasian Chalk Circle was extremely popular among the area’s theater community and was remounted several times, even after Sills graduated.

After leaving the university, Sills and some of his college friends moved into a converted Chinese restaurant near Hyde Park. His “diverse and multi-talented bunch of misfits”–many of whom were destined to become luminaries in the theater community–founded The Playwright’s Theater Club. It was one of the first DIY venues in the city. The company stressed ensemble-based creation and they used many of Spolin’s games during the rehearsal process. The actors lived communally off each show’s ticket sales. Each performer took home five, 10 or 15 dollars based on need. Many even lived in the theater itself, in alcoves separated from the performance space by curtains. Though their audience were largely members of the local literati, the theater remained successful for over 18 months. They even joined the Actors Equity Association, the professional theater guild, by the end of their first year, which guaranteed a minimum salary for each actor.

The Playwrights Theatre Club remained successful for 18; then, it was forced to close. The official reason or justification was one or a series of fire code violations. However, those within the company pointed to political meddling. The closing took place in the 1950s, a time of intense social paranoia. Europe was torn betwixt economic systems. In Washington D.C., the House of Un-American Activities Committee was tearing through the American political and cultural sphere in a hunt for foreign subversion. In this context, the participants of Playwrights Theater Club were suspect. They were educated Jews[2] willingly living in poverty who performed the works of playwrights like Bertolt Brecht, who fled to East Germany after openly mocking the Committee of Un-American Activities[3]. Regardless of cause, the Playwright’s Theater Space was shuttered. After the company lost their venue, they attempted to reform in different locations, but found the spark that drew them together had gone the way of their space. Still, the theater would form an important grounding for the companies created throughout the rest of the 1950s.

After the closing of the Playwright’s Theater, many of its original members formed a new company, The Compass Players. The company, with Paul Sills as its director, continued many of the practices pioneered by its predecessor while developing its unique, creative vision. Compass originally billed itself as a Commedia dell’Arte company, placing it within the creative tribe of the mendicant Renaissance companies that first established theater as a profession in the West. Like those prototypal performers, Compass was local and grounded. In contrast to the established companies in Hollywood and on Broadway, Compass sought to deal only in works that were immediate and local. Their shows were based around the “Living Newspaper.” Performers picked articles from that day’s newspaper and in 10 minutes, devised a 45-minute performance for the audience. Performing in a converted bar near Hyde Park, they sought to “point in the direction society is heading.” They became the darlings of both the University cognoscenti and a developing class of young, educated urban professionals.

While its theatrical style would eventually revolutionize the performance-making process in the city, its casualness forever altered the role of the audience. In contrast to the formality of the downtown theater audience, Compass emphasized a casual viewing experience. The dress code was casual and food was served during the show. In this way, Compass continued the decades-long legacy of casual and accessible dinner theaters that had existed, to the sneers of the Eastern elite. The company was, in this way, the first professional theater grounded in the populism of Chicago culture. Though it, too, shuttered after only 18 months, it offered a cultural contribution of considerable merit.

Considering the revolution that The Second City brought to the city, it is important to note that by the time that theater was founded, most of its revolutionary ethos had been established by its predecessors. Playwright’s, for instance, developed the concept of devised and ensemble-created theater. Compass brought improvisation and informality. Though Compass, like Playwright’s, ended after 18 months, most of the major collaborators in the company remained together and developed a new company, which was destined to last for significantly longer. They named their new company after Liebling’s series of New Yorker articles satirizing Chicago culture: The Second City.

On its surface, The Second City, founded in 1959, was similar to Compass. They continued to use many of the improvisation games developed by Spolin. Each company member owned a portion of the company, and whenever they left, they were expected to sell their share to their replacement. The audience, who were there to eat and watch a show, dressed casually. The performers took a suggestion from the audience–generally political–and devised an original set each night. In time, they developed some of their skits into the revues that soon became famous.

The companies did differ, however; reflecting the growth of the artistic temperaments and business acumen of those involved. Whereas Compass conceived of culture as a character, capable of being influenced, Second City regarded culture as a mindless and chaotic automaton. Whereas Compass created its work primarily on the South Side, Second City bought a space in Old Town, not far from its current headquarters.

The greatest difference between The Second City and its predecessors was dramatic. From its first night, they sold out nearly every evening. Their theater had 125 seats, but they regularly squeezed in 130. Within a year, celebrities were making pilgrimages from the coasts and the company was bringing its work to the world’s performance center. In 1961, the company took a tour to Broadway, earning a Tony nomination for one of its cast members. They had become rousingly successful. More importantly, the company had taken the final step in a path that began with Depression-era immigrants, improvising out of necessity in order to compensate for their newness to a culture and language so contrary to their own.

Over the succeeding 60 years, the company continued to develop and expand. It nurtured stars, developed its own TV programming and expanded coast to coast. In the process, many of the original developers of the theater left the company. Paul Sills, one of three founders and the director of the company’s first six revues, left by the mid-1960s. With his mother, he founded Game Theater, where audience members were welcomed on stage to participate in Spolin’s games. Spolin herself had been director of workshops at Second City, until Sills’s departure necessitated her own. She eventually moved to Los Angeles, where she formed a theater school. How they reached such a level of sustained success is a completely different story. For Chicago’s experimental community, The Second City’s best success came early, with a bunch of poor Jews living above a Chinese restaurant, who had the will to challenge the stifling wind of culture.

Tune in next month for another Chicago experimental history column by our DIY theater and performance contributor Felix Abidor.

[1] The University of Chicago is also known for being the breeding ground of thousands of worthy artists, authors, mathematicians, scientists, etc. Still, when one composes the list of the most fun universities in the country, the University would rarely pass muster.

[2] Here, we must take the time to place Jewishness as an ethnic group in historical perspective. Jews have long had a complex and shifting balance between privilege and isolation in the United States. While the modern Jew is often considered white both of their own accord and in large majorities of society, it has not always been that way. In the early 20th Century, Jews were largely isolated in their own neighborhoods, speaking languages that they brought from Europe and elsewhere. Meanwhile, anti-semitism was rife in both intellectual and public life. In the early 1950s, Congress, over a veto by Harry Truman, renewed an immigration quota on Jews. Fleeing the remnants of the Holocaust in Europe, it would be years until Jews were accepted by the mainstream. The writer of this piece is Jewish.

[3] Bertolt Brecht speaks in the House Committee on Un-American Activities.

Shocking that there is absolutely no mention of David Shepherd, co-producer of Playwrights Theatre Club and Compass. In fact, Compass was David’s idea. Without David’s contribution to improvisation, there would have been no Second City,. This article is poorly researched.