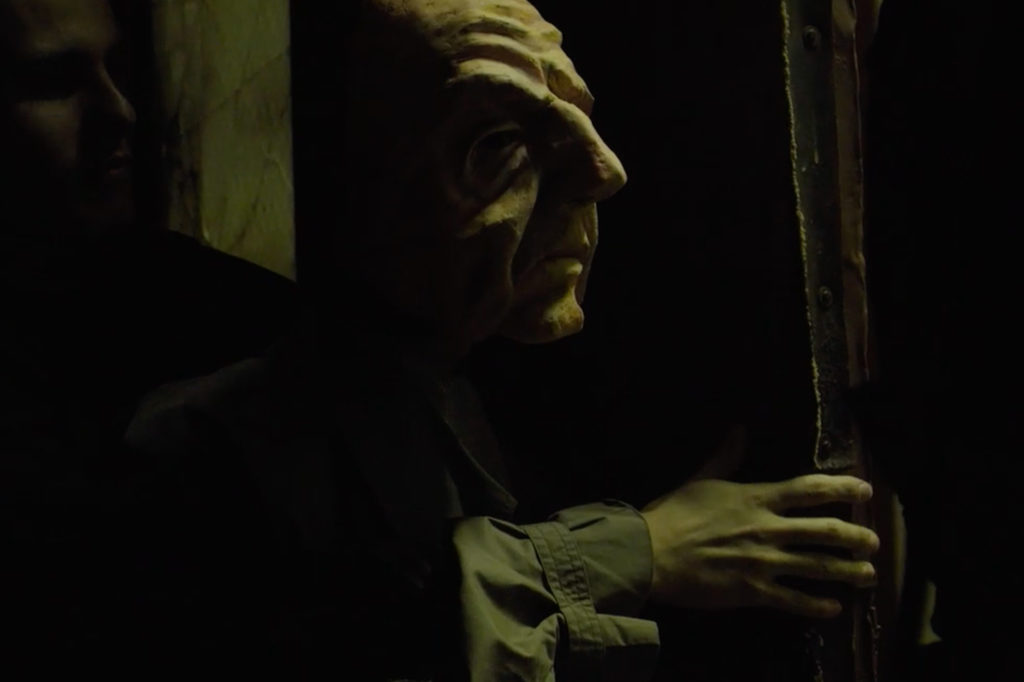

Pictured above: The Walls of Harrow House/Photo: Chrystyne Kozol

A week before their opening, I had the opportunity to talk with the co-artistic directors of Rough House Theatre Claire Saxe and Mike Oleon to discuss puppetry in Chicago, as well as their new show The Walls of Harrow House. Saxe co-wrote The Walls of Harrow House with Mark Maxwell and Oleon conceived and directed the project.

・・・

Is this your first time creating a haunted house experience?

Saxe: Yes.

Without spoiling everything—is it just like a regular haunted house or is there a plot to guide through the house?

Saxe: Yes there’s plot. It’s like… Halfway a haunted house, halfway a play?

Oleon: I don’t know, it’s like a pretty solid 50/50, maybe 60/40 leaning towards play… immersive theater is challenging so many of the conventions of regular play right now, and all those conventions have always been in haunted houses, but now they’re starting to get normalized for theater. It’s not so shocking [now] to walk anywhere you like in a regular play. We’re using the tools of a haunted house to make a play. So ultimately. The audience will have pretty much free reign of the space once the show gets going. In terms of narrative elements, our hope at least is that at least there is more narrative than any one person will be able to experience in a single go-around.

Saxe: It doesn’t have the same linearity as a haunted house. We’re trying to alleviate that uncomfortable feeling in haunted houses.

How was the process? How did you create this concept by creating a puppet haunted house?

Oleon: Because puppetry is so interdisciplinary, there are different inception moments for different parts of the haunted house, and this is a large enough project to absorb all of them. Just to start with. there is the story itself, which came independently of some things—but then there’s the puppetry, and the idea of putting puppets into a spooky situation with the audience. In previous plays, we had puppet moments, and a puppet would do things that were utterly horrifying and often completely out of character. That is not going to work for this play, but we’ll write that down and come back to it. Over the years, we built a collection of strange, spooky things that we know puppets are well-suited to do. We’re going to release it on people.

Why is puppetry so important, especially in the artistic community?

Saxe: Puppetry means a lot of things for a lot of people. For Rough House, what is important and exciting is that it is necessarily cross-disciplinary, so any piece of puppetry is, at the same time, as much a piece of visual art as it is performance. It makes you think visually, in movement language and spatially, rather than always putting text first, which is what happens to a lot of theater in Chicago. It forces you to collide with and challenge expectations for several different art forms. That’s exciting to us.

What’s a quick summary of the show so when readers see it they get a good idea before they enter your space?

Saxe: We have created a fictional famous architect named Milton Harrow, loosely based off of Frank Lloyd Wright, or some of Frank Lloyd Wright’s crazier ideas—

Oleon: Or paternalistic ideas of the architect-knows-best, in all cases.

Saxe: So, Harrow House is his famous home and studio. It has been closed off to the public for many decades and is now open to the public. As they arrive, the audience is told they are honored guests who are longtime supporters of Harrow and they are there for some purpose. The show starts as a tour of the house that is guided by two leaders of the Harrow community, and a few minutes into it, something in the house goes wrong and the tour guides apologize and leave. The audience members are left to explore the house and pick up the narrative on their own terms.

Have there been any obstacles you had to overcome?

Oleon: Making a new work is an exercise in overcoming friction. It’s also full of really incredible surprises. So people don’t have a shared vocabulary for creating.

As big as it would like to claim credit for, even the puppetry scene is small. This is the biggest show we’ve ever made as a company and by large, everybody is coming to puppetry for the first, second or at the very most, third time. You don’t have people who went to school for puppetry or have been training for it their entire lives. So there’s a lot of learning and discovery.

And you start to see people make puppet-based decisions, rather than hoping for somebody else to hand them the answer, which is really neat. I think actors can come in and need to have more things handed to them from the beginning, like this is what this object can accomplish or here’s what we are expecting out of it. You learn what this toy does and what is fun with this, and that’s what a puppet show is like. You learn to make something move in a way that delights you and feels true to the object. Everyone is starting to get comfortable and better with that.

Saxe: It’s big. It’s just bigger than we’ve ever done. We have a cast of 12 performers and 12 to 15 design and production people, which is almost twice the size of anything we’ve ever done before and the budget is twice the size of anything we’ve ever done.

It’s just a drunken scale for us. Which is exciting, and coordinating is fun but also challenging. So, what’s happening in this scene? That depends on what the puppet is doing, but the puppet designer says it depends on how does the puppet interact with the architecture? And the scenic designer is like what is happening in the scene, and that depends on the puppet—so it becomes this triangle! So out of the process comes what is necessary. We’re learning how to navigate it better. Here’s the thinking and we’ll be better at it.

Did the actors in your company have training in puppetry or did you have to teach them, or did they have the background?

Oleon: Very few.

Saxe: There are a couple we have worked with before, so we have done puppetry with them. I think there are two cast members who have worked with other companies in Chicago, who have come through Red Moon or Puppet Wonder Wagon, or work at Chicago Children’s Theatre and have done some puppetry, so people are picking up little bits and pieces.

Oleon: Everyone has puppet-adjacent experience. They have an interest in physical theater or clown or circus or visual arts… there’s a lot of actors who have craft in their lives. Not exactly puppetry per se, but helpful on the path to playing with puppets.

What inspired you to do this? Who were your inspirations?

Oleon: Frank Lloyd Wright has made some very creepy looking houses. They’re horrifying in some cases. This isn’t true of all of them, but a lot of them sit on the market for a long time because people don’t want to live in them. They are stunning, beautiful things to look at, but they are not the most comfortable things to live in.

I was on a tour with my grandmother of Hollyhock House in Los Angeles. She wanted to take me for years. As we went through, they kept talking about all the peculiarities of the house, like this part of the house sags a little bit because there’s poor air flow, because he wanted a ton of glass in this certain part. The big one that struck me was the tiny kitchen. On the tour, they said he didn’t spend a lot of time in the kitchen and he didn’t really see the need for comfort for people who spent time in the kitchen. And I thought, “That’s really fucked up.”

And that was the seed of everything. How do we spend so much time worshipping these great people who accomplish all sorts of stuff, who also have the potential for either these neglectful or cruel tendencies? I think it felt like there was a story there.

It’s true of a lot of his houses. Falling Water wouldn’t exist without constant maintenance—it would turn into mush and fall into the river. But people think it’s the greatest piece of American architecture.

And in the case of the haunted house itself… What happens in a lot of his houses, is that wood rot or mold will creep in. It has a strange, sinister quality, and that is our gateway to the supernatural in Harrow House—because of neglectful design or hubris in design, it allows mold to come in, the mold is chaos, and it allows these monstrous transformations. It allows these weird puppet creatures to be born.

Why should people come to see this show, compared to other Halloween shows that are coming out this month?

Saxe: It’s been important to us to not simply make it a play and also not simply a haunted house. We hope it is fun and creepy and scary, but also, we’ve created a story and characters that have meaning to us. I think of what Mike was saying with the inspiration of Frank Lloyd Wright and the horrors of people we see as great.

Oleon: Haunted houses are fun. They’re thrilling. For me, they’re some of the most fun things you can possibly do. Even a crummy one can be fun in its own weird way, or there can be a room where people pour all kinds of time, love and moments of inspiration.

In theater, you have this incredible tool that opens people up and gets them excited for something, and cuts into some of their most primal senses, which is fear. That seems like a fantastic storytelling tool, so we can examine humanity under a different lens, all while people are in a different, immersed state.

Saxe: Usually, puppet theater looks best on a proscenium stage, so there’s a rigid relationship between the audience and the action on the stage. It feels like a fun and exciting artistic challenge for us, and hopefully an exciting thing for the audience to experience an art form that’s spatially different but also invites a different kind of engagement.

・・・

The Walls of Harrow House performances occur Thursday through Saturday at Chopin Theatre, 1543 West Division Street through November 3. More information can be found through roughhousetheater.com and via email at info@roughhousetheater.com.

Be First to Comment