Pictured: CBLDF Deputy Director Alex Cox

Of the many panels throughout the Chicago Comic and Entertainment Expo, none laid bare the crucial role of comics in social and political discourse in as much historical detail as Comic Book Legal Defense Fund’s Alex Cox’s “Comics Change the World: History of Activism in Comics.”

The lecture spanned the regular amount of time for a panel in one of McCormick Places many large back rooms, but ran the gamut of comics with political messaging through the last 100 years.

Cox points out that a lot of these comics are more relevant than we realize, especially the ones from the 20’s and 30’s that chronicle the plights of the working class and the debate being had within the working class. The example here is the International Workers of the World’s own Mr. Block.

Cox points out that a lot of these comics are more relevant than we realize, especially the ones from the 20’s and 30’s that chronicle the plights of the working class and the debate being had within the working class. The example here is the International Workers of the World’s own Mr. Block.

“Mr Block is a hilarious piece of activist work,” Cox said. “This is the done by the Industrial Workers of the World, otherwise known as the Wobblies. It ran in The Industrial Worker, you can occasionally find reprints, and features Mr. Block who is a character who is against unions, he’s against the worker, he’s antisocialist and he’s constantly getting abused by people in authority.”

Comics also were regularly used as propaganda, as Cox points out. After moving to the era of FDR and World War II, one audience member asked for clarification for whether or not these comics were before or after America’s entrance to the war, to which Cox made clear the differences between the comics he had on display.

Some comics were before America’s entrance into the war, with clear appeals to American sentimentality, while others are clearly after America’s entrance to the war, given that the comics made clear references to the need for buying bonds to support war efforts.

Cox also pointed out that a lot of activist work in comics had underground presence. One example of that was a comic called Lenny of Laredo, which had deep ties to the free speech movement.

“Lenny of Loredo is basically a thinly veiled history of Lenny Bruce,” Cox said.

“Lenny of Loredo is basically a thinly veiled history of Lenny Bruce,” Cox said.

Lenny Bruce was a famous stand-up comic and satirist that made open critique of social policy in the 50s and 60s.

According to the official Lenny Bruce website, he was renowned for his open, free-style and critical form of comedy which integrated satire, politics, religion, sex, and vulgarity. His 1964 conviction in an obscenitytrial was followed by a posthumous pardon, the first in New York State history, by then-Governor George Pataki in 2003. He paved the way for future outspoken counterculture-era comedians, and his trial for obscenity is seen as a landmark for freedom of speech in the United States.

“It’s one of the earliest what we would call underground comics today, and it was tied into the free speech movement in Berkeley,” Cox said. “This was absolutely built out of the student activist movement. It was distributed by students and it was inspirational because Lenny Bruce at the time was a very well-known free speech figure.”

Race and Comics went very much together as early as the 50s. Cox points out that it was not just Green Lantern, Luke Cage, and Black Panther. EC, first Educational Comics, then named Entertaining Comics, has become the home of an infamous story in which the editor, William Gaines, ran a story that featured a black man as the main character in a story of space travel.

Noted by comics historian Digby Diehl, Gaines threatened Judge Charles Murphy, the Comics Code Administrator, with a lawsuit when Murphy ordered EC to alter the science-fiction story “Judgment Day”, in Incredible Science Fiction #33 (Feb. 1956). The story itself was “objected to” because of “the central character being black”.

According to Diehl:

“This really made ’em go bananas in the Code czar’s office. ‘Judge Murphy was off his nut. He was really out to get us’, recalls [EC editor] Feldstein. ‘I went in there with this story and Murphy says, “It can’t be a Black man”. But … but that’s the whole point of the story!’ Feldstein sputtered. When Murphy continued to insist that the Black man had to go, Feldstein put it on the line. ‘Listen’, he told Murphy, ‘you’ve been riding us and making it impossible to put out anything at all because you guys just want us out of business’. [Feldstein] reported the results of his audience with the czar to Gaines, who was furious [and] immediately picked up the phone and called Murphy. ‘This is ridiculous!’ he bellowed. ‘I’m going to call a press conference on this. You have no grounds, no basis, to do this. I’ll sue you’. Murphy made what he surely thought was a gracious concession. ‘All right. Just take off the beads of sweat’. At that, Gaines and Feldstein both went ballistic. ‘Fuck you!’ they shouted into the telephone in unison. Murphy hung up on them, but the story ran in its original form.”

Moving into the present day, Cox makes note of highly politial works like The Boondocks and Get Your War On, but also makes note of comics that were able to actively make change through fundraising.

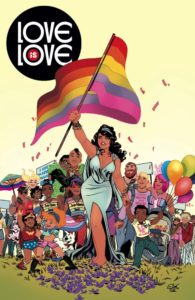

The example of this Cox points out was the recent project Love is Love, an anthology made in the wake of the attack on Pulse Nightclub in Orlando.

The example of this Cox points out was the recent project Love is Love, an anthology made in the wake of the attack on Pulse Nightclub in Orlando.

According to the IDW Publishing website, the anthology was co-published by two of the premiere publishers in comics—DC and IDW, this oversize comic contains moving and heartfelt material from some of the greatest talent in comics, mourning the victims, supporting the survivors, celebrating the LGBTQ community, and examining love in today’s world.

All material has been kindly donated by the writers, artists, and editors with all proceeds going to victims, survivors, and their families.

You can learn more about the work that the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund does on their website here.

Be First to Comment