The race to win over the hearts and minds of Amazon’s elites has been well publicized over the last year, the most notable feature coming from John Oliver’s episode on the topic.

As for Chicago, the city has teamed up with state officials to put together an aggressive bid, including multiple tax breaks that are estimated at 2.25 billion dollars.

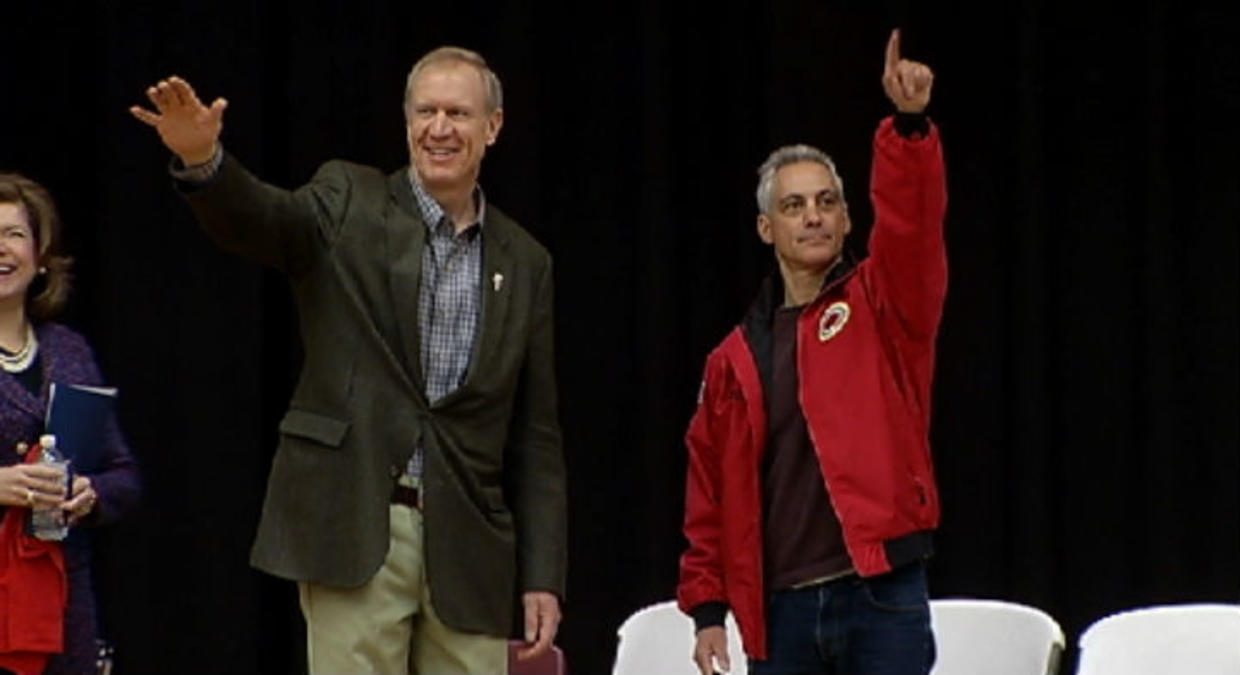

It’s rare that city and state get along so well in Illinois, especially with Emanuel and Rauner’s storied rivalry. Rauner has blamed Emanuel in the past for almost all of his failures to pass a budget in his first term, while Emanuel has helped to draw the line between city and state in the continued issues surrounding school funding.

Why this partnership has gone into full swing now has been chronicled in a series of articles by Ben Joravskey in the Chicago Reader. In a piece for The Reader back in September, Ben Joravskey highlight’s Amazon’s request to cities looking to house its HQ2, as it’s called, pointing out that Amazon has asked for cities to show their tax incentives up front while not solidifying what wage expectations will be.

“Please note that the actual average wage rate may vary from the projected wage rate depending upon prevailing rates at the final location,” the report states. “All job numbers, categories, and salaries contained herein are estimates/projections and are subject to change. The jobs will likely be broken down into the following categories: executive/management, engineering with a preference for software development engineers (SDE), legal, accounting, and administrative.”

In the following piece, Joravskey highlights the long history Chicago has had with this debate particularly, highlighting the Chicago 21 plan put together by big investors to centralize production in Chicago.

“The section on Cabrini-Green is particularly revealing,” Joravskey writes. “Back then, the Chicago Housing Authority project around Division and Orleans was packed with thousands of residents. The Chicago 21 planners realized upscale development in the area would be hampered by a complex of government- subsidized residences. Yet they were astute enough to realize they couldn’t call for its demolition without setting off a firestorm of protest.”

In response, the city promised that in no case should [development] result in displacement of existing residents for financial or other reasons.

“Obviously, the city broke that promise years ago, when it demolished the project’s high- rises and scattered most of the residents to the wind,” Joravskey said.

Chicago’s HQ2 bid offers Amazon two sites not far from the former housing development, including Lincoln Yards and the River District.

This holds significant relevance in a conversation being had within Chicago and most major urban areas, the one of gentrification and for pushing for development without displacement. The most recent large-scale piece of that discourse coming from gubernatorial candidate Chris Kennedy.

Kennedy recently called out Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel as having a strategy in place to support gentrification.

“I believe that black people are being pushed out of Chicago intentionally by a strategy that involves disinvestment in communities being implemented by the city administration, and I believe Rahm Emanuel is the head of the city administration and therefore needs to be held responsible for those outcomes,” Kennedy said.

In Chicago, displacement and race are intrinsically linked. This is well documented in Ta-Nehesi Coates’ now famous The Case for Reparations.

Amazon does its own report on diversity internally, and the most recent data in 2016 showed that the company’s workforce was primarily male (61%) and management positions were 66% white folks.

Black folks made up 21% of Amazon’s global employees, but only 5% of its managers. Latinx folks comprised 13% of the total workforce and only 5% of manager positions. Asian folks were the only group to have a larger percentage of managers (21%) as compared to its overall percentage of workers (13%). Women represented 39% of the workforce and 25% of the total number of managers.

Amazon’s history of how development takes place is also well-documented in Seattle, the location of its first headquarters.

In an article written by Timothy Egan in The New York Times highlighting what Amazon has done for Seattle, the answer is raised incomes means housing rates have skyrocketed.

“They have 40,000 employees here, who in turn attracted 50,000 other new jobs,” Egan said. “They own or lease a fifth of all the class A office space.But median home prices have doubled in five years, to $700,000. This is not a good thing in a place where teachers and cops used to be able to afford a house with a water view.”

“They have 40,000 employees here, who in turn attracted 50,000 other new jobs,” Egan said. “They own or lease a fifth of all the class A office space.But median home prices have doubled in five years, to $700,000. This is not a good thing in a place where teachers and cops used to be able to afford a house with a water view.”

This is also well-documented in Seattle’s rise in homelessness from 2012 to 2015. According to Curbed, A new report by the Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness (ICPH) found that Washington State’s homeless student population grew by nearly 30 percent between 2012 and 2015.

“The money and growth have meant more density, and an end to many mom-and-pop shops,” Doug Ressler, an analyst at real estate technology firm Yardi said. “Seattle has always prided itself on being a friendly, lifestyle town. But that’s going out the window.”

“Don’t give away too much too quick, that’s what I feel like Seattle did,” Ressler said.

Emanuel claims that Amazon will bring $341 billion in total spending over 17 years, including $71 billion in salaries, and supporting an additional 37,500 jobs in the region annually.

Be First to Comment