Pictured above: Audra Jacot in front of a collage of her work // Photo courtesy audrajacot.com

In the midst of an uninspired period, artist Audra Jacot decided to build the word skeet in multiple fanciful fonts and in her favorite medium, neon. Skeet, according to the Urban Dictionary, translates to mean when a man “gets there” sexually.

“In my brain, I thought it would be beautiful,” Jacot said.

So in a neon-building lab, the School of the Art Institute alumnus blew into faintly colored, heated glass tubes to create the letters, trusting her metronome-like sense in order to perfect the swirls of the t’s and k’s.

When she explains the process, it seems enigmatic and all-consuming, like glass-blowing taken to an untapped level.

“Making neon is not exactly glass-blowing, but it’s glass-bending,” Jacot said. “You let gravity fall, and then you do your bending.”

She pushes the gas corresponding to the sign’s desired color into the tube afterwards to burn out leftover impurities and give the piece its effervescent glow. She likely has a burn or two as evidence of the time spent. (And she has a Twitch stream of her making one for extra proof.)

The kicker is Skeet, Skeet, which is what she titled the crass signage, is not a deviation for her work’s general theme. Rather, it’s a staple.

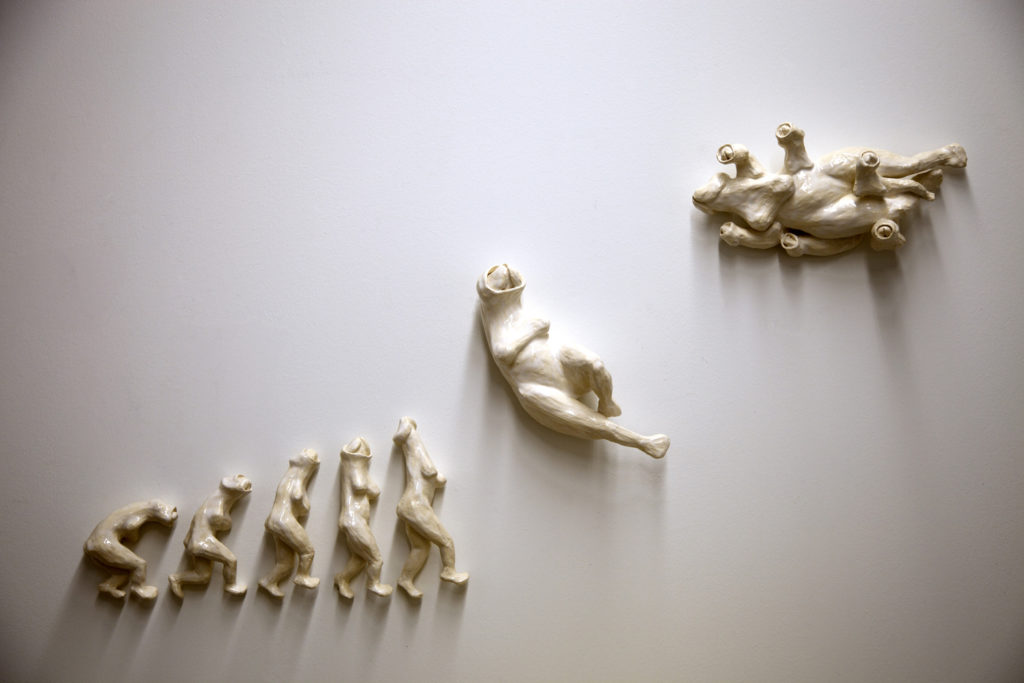

The word choice fits firmly into the sexual overtones of Jacot’s art that is consumed with adult themes, colorful THOTS, and breasticles, a fusion of male and female genitalia she sculpted and named. Following a Mormon upbringing in a Filipino household, Jacot may be the last person anyone predicted to fall into her profession. But she took advantage of her move to Chicago from California for graduate school to explore sexuality in creative mediums (namely, neon and clay reign as her go-tos).

Her mission melding art and raw sexuality is adventurous. Jacot will admit it’s funny.

“I have a sense of humor,” she said. “I don’t want my stuff to be ‘woe is me’ or that I’m sad because then it would make me sad.”

In 2014, her mother called her a pervert and reprimanded her with silence for parading her initial raunchy creation, the breasticles. Even Jacot herself feared being branded “the penis girl” for the work, but she cowered away from being categorized rather than slut-shamed as she was. From her mother’s comments grew Jacot’s anti-hatred lettering. In a sharp and inspired reaction to negativity, she animates neon signs that reverse the vocabulary of oppression into that of empowerment.

She boldly created the word PERVERT in red lettering while her and her mother still weren’t speaking. People responded with supportive comments, posts dedicated to her art, and snappy jokes––“that’s me,” some said.

“When people identify with it, it’s like I’m not alone, I’m not a pervert,” Jacot said. “These people are shamelessly proud to be a pervert and take a picture with it and post on social media how perverted they are.”

Neon signs brandishing words like fag, flaccid, slut, and eat me, as well as variations of the eggplant emoji and lit imitations of childrens’ monster drawings, have followed in the years since the pervert design.

Her creations, bordering on the edge of social appropriateness, have garnered high-profile praise. A rose-tinted “ugh” shined brightly in the background of the Emmy-nominated web series, Brown Girls. She’s responsible for the sultry purple title card of Netflix’s Easy and another one for an acquaintance’s movie, Makeout Party. Jacot even dressed statues in Lollapalooza’s VIP lounge and countless shops, speakeasies, and installations in the city area.

The source of her widespread acclaim, however, began by accident. A younger Jacot was floored by “fabricating” and “putting together circuits” and set out to get a work-study job in the electric-kinetic lab at SAIC. She only fell into neon per the advice of the professor who was interviewing her. “I remember being frustrated at first,” she recounts of her early neon days. “It’s not like welding metal. It’s a completely different material.”

Her non-conventional career deviates from the normalcy of art, if such a thing exists. She does not expect her work to be showered with gazes in galleries. Instead Jacot’s neon signs are commissioned for exhibits, films, and stores or created by her own volition. But the SAIC campus audio-visual manager said she’s “not interested in being a signmaker” and sticks to neon on the side. She refuses to take it up as a job out of fear of developing a hatred for a pure and passionate love.

Through her years of welding, neon has grown in the mainstream. It sells in stores like Urban Outfitters and slowly began to appear more and more frequently on film sets and in reality. Jacot sees this change, and she welcomes it. Rather than seeing the arrival of mainstream attention as a force of corruption driving through her chosen medium, the artist views the growth as a newfound acceptance of a medium often forgotten.

“It is becoming more accessible to people,” Jacot sad. “People are realizing that instead of having lamps in their rooms, they can illuminate with neon…that makes people want to have it.”

Regardless, neon isn’t her only medium.

Jacot’s breasticles were sculpted with clay, a material she has repeatedly used to shape genitalia to tell stories of love, lust, and humanity. And her artistic origins root themselves in drawing, seeing that she wanted to become a comic book creator as a child. Thankfully, that dream grew to fruition in her recently debuted adult activity book featuring coloring pages, mazes, and games.

As her work highlights storefronts, television sets, and hotel walls––locations far from where people oft view art, Jacot’s creations are fusing with a multimedia world, a community removed from the sometimes pretentious nature of the elite art world. Her creations clearly have her fingerprints embedded in them, in the curves of her clay penises, and in the colors of her neon signs.

In an upcoming project, Jacot, alongside a handful of colleagues including neon instructor and former professor Greg Mari, are introducing this handcrafted quality in neon to a larger swath of creators. They rented out a space in the city to establish a co-op program for amateur and experienced neon artists where they will provide classes and offer opportunities to rent out equipment needed in the art form.

Jacot beams at the chance to spread her passion to a new group of neon makers or rekindle a similar love to her own in other artists.

“In art school, I would see what got people interested? What’s in galleries?” Jacot said. “I realized if I don’t do something that’s genuine then, I’m not going to be interested in it at all. And I’m interested in this…the idea of building a community”

Find out more about Audra on her website, Facebook, and Instagram. Listen to Scapi Radio’s podcast with Audra here.

Be First to Comment