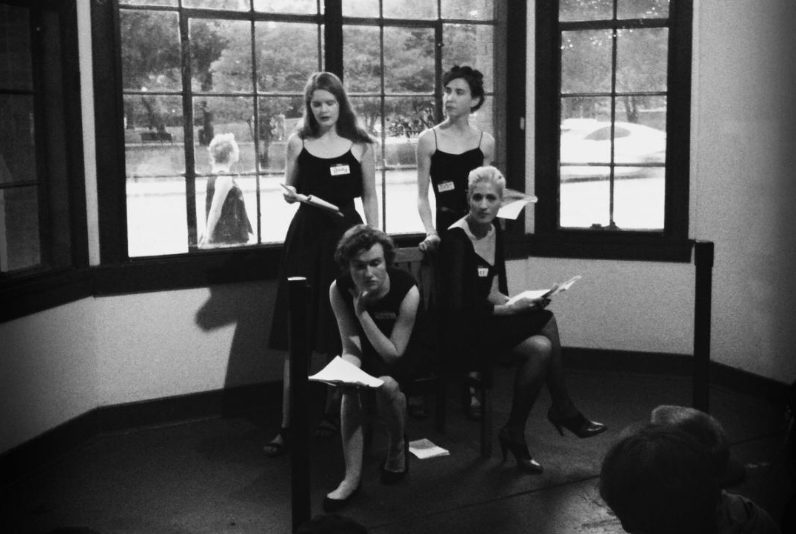

Pictured above: Sara Zalek, Eileen Colwell, Kathleen Rooney, Maryse Meijer and Eleni Sauvageau in The Blue Hour/Photo: Eric Plattner

Editor’s Note: This is an expression by FirstName LastName in response to The Blue Hour in an experiential and descriptive form; it is followed by information about the work and process.

・・・

When I agreed to review The Blue Hour, a production directed by Chicago unnatural theater connoisseur, Logan Barry, I wondered what exactly unnatural theater might mean. Full disclosure: I have been an admirer of Barry’s work for a few years now, and have had the opportunity to work beside him as both a dear friend and a member of Poems While You Wait. But my admiration for Barry did not temper my hesitation as I approached the Comfort Station on May 25. Perhaps that is because in our contemporary climate, dystopias feel eerily familiar. Or perhaps it was Barry’s intent—to walk us through living language, to breathe the verse and meter, and to become the poetry.

Because this work was an adaptation of an adaptation, I was forced to confront a sort of revisionist history. The Blue Hour could not exist without its relationship to the words that precipitated it. It was rooted in Elisa Gabbert’s collection, L’Heure Bleue, or the Judy Poems, which had been inspired by Wallace Shawn’s, The Designated Mourner. Consequently, the production was like looking through a kaleidoscope. At once, it queried authorship, alternative facts and alternative truths.

In Shawn’s original, intellectuals are put to death in the face of oligarchy. The protagonist, Jack, discovers that his abandoned wife, Judy, has died on a chair, “with her head at that rather odd angle,” by reading about it in the paper (781). Yet, there is a distinct lack of mourning despite the play’s namesake. Judy’s murder is intentionally understated, a horrific use of litotes, to tap into the trope of our own dissociation to the news. Consequently, Barry’s reimagining fixates on the climax of Judy’s murder with an intimacy and immediacy that forces us all to confront our own mortality.

When Gabbert set out to write L’Heure Bleue, she was fascinated by Shawn’s original, and yet, Aaron Angello explains eloquently in the introduction to her collection, “[Judy’s] character she felt, lacked a depth that the male characters had…Elisa began exploring the mind and history of the character in a much more nuanced way” (5). Her revisionist poetry explores the intersection of alternate facts and feminist identity prior to the Time’s Up and Me Too movements, but it has never felt more relevant. In Barry’s adaptation of the adaptation, we are confronted by Judy’s multiple personalities, masks, and relationships to her own past and future. Barry incarnates the multiple cognitions of Judy at center stage by quite literally presenting us with multiple Judys. In essence, The Blue Hour brought Judy to life five times over, only to kill her all over again.

*

As we entered the small cottage, the first Judy, played by Eleni Sauvageau, greeted me and, like any good, sophisticated hostess in a fictional dystopian oligarchy, she presented a paper plate of pineapples stabbed with toothpicks.

“Pineapple has an enzyme in it that erodes your taste buds,” she offered as an explanation.

I could have sworn she had said, “murders your taste buds.” After all, there was something murderous in her manner. But then, I heard her repeating her mantra time and again as she greeted all guests identically, masking her cynicism behind a plastered smile. So, it was my own imagination that had wandered from pineapple to murder.

Another Judy approached me, played by Eileen Colwell.

“Can I tell you a secret?” she asked. Without waiting for my reply, she embraced me and whispered in my ear, “I see death everywhere.”

I looked at her, a bit haunted, and we locked eyes. She maintained a deadpan and empty gaze.

“What color is it?” I asked.

“Blue.” Of course. It was, after all, the hour of blue.

“What does it look like?”

“Pale and peaceful.”

“That doesn’t sound very frightening.”

“I never said I was frightened.” As she said it, the ghoulish blue light from a film display, a work by Jessie McCarty, Barry’s co-director, lit her face like an ethereal fire.

Next, Judy #3, Kathleen Rooney, asked me about my past. She bore a serious countenance, sitting behind her typewriter like it was plate armor.

“What does this smell remind you of?” She passed me a small capsule filled with herbs and a must that reminded me of homesickness, but for a past I had never known.

I responded simply: “Childhood.”

She clacked her keys.

“Are you afraid of the future?” she queried.

“Horribly,” I said, attempting to meet her eyes.

“Enjoy the party,” she said flatly, and dismissed me back into the crowd where I seemed to disappear.

A parallel to Rooney’s nostalgia, another Judy played by Maryse Meijer, read Tarot cards and spoke of the future.

“Reading the cards is just like writing a story,” she explained, as she told me I was a veiled woman, driven by the artistic moon.

“What’s this one?” I asked of a woman, shivering outside a window, looking longingly in at the warmth and the light.

“It’s part of being an artist,” she explained. “But the thing is, you can always go into the warm room. You don’t have to wait outside.”

*

As though an imaginary bell had tolled, all the Judys rose and aligned in the center of the space. They performed Gabbert’s poetry, their voices bleeding into each other, yet maintaining a sense of autonomous distinction. Throughout the evening, a Judy played by Sara Zalek had been effervescent, bursting into fits of inappropriate laughter. As the mood shifted in the room, I watched her undergo a terrific transformation.

Meanwhile, one of the Judys, facing a unique perspective of the room, lamented: “After a seizure, / my epileptic friend says / he recognizes strangers. / Every face looks familiar, / the only sign that something’s wrong” (51).

I looked about the sea of stranger’s faces. None of us could deny our loneliness.

Another Judy concluded, gazing from another strange angle, “Once over dinner I misheard / my father and everafter have referred / to Jack’s ‘violet moods’” (79). And just like that, all at once, we were all thinking about murder because of a single pineapple.

It wasn’t until Sara Zalek sauntered by the bay window, moving slowly beside the speeding cars, that I realized she had left the room undetected during the performance. She walked aimlessly like she was looking for something out there in the traffic. Occasionally, she re-appeared like an apparition, framed by different windows, looking lost yet peaceful. When she finally re-entered the space, she marched into the center of the room, scattering the crowd like pigeons. She began to convulse, and papers erupted from her fingertips, bearing the nostalgic writings recorded by Rooney. Audience members snatched up the memories as they rained across the room. Slowly, Zalek transitioned from an awkward angle on a chair, forcing us to confront Shawn’s vision, to a final resting place on the floor. Her eyes were wide open. Watching her, our eyes were wide open too. And so, in the blue and humid night, the people became the poetry.

・・・

As a part of their month-long series Force & Motion, the Runaways Lab Theatre presented The Blue Hour, an art installation cum-theatrical performance that investigated desire and memory in the age of mass surveillance. The Comfort Station was transformed into a zone of multisensory experience and reflection with a cast of writers, dancers and philosophers.

The Blue Hour performance occurred on May 25 at The Comfort Station, 2579 North Milwaukee Avenue. To learn more about the Force & Motion series and other upcoming performances by Logan Barry and The Runaways Lab Theatre, visit runawayslab.org.

Be First to Comment