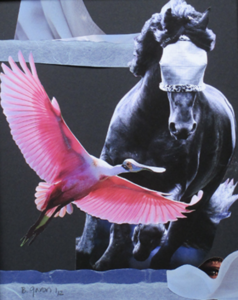

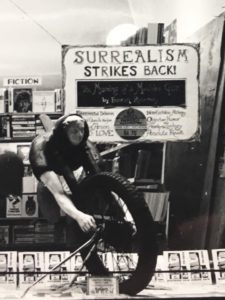

Pictured above: Capture from the 50th-anniversary commemoration of the 1968 Chicago Surrealist Protest Show at the exhibit REVOLUTIONARY IMAGINATION: Chicago Surrealism from Object to Activism in June 2018/Photo: Featured on dadachicago.com

Penelope Rosemont, one of the artists at the forefront of the Chicago Surrealist Group in the 1960s, now lives comfortably in Evanston, IL. One of the final remaining practicians of a movement whose members—and history—are slowly disappearing, she was surprised about a month ago to hear that her name was in the news once again. A new article about her work, published by writer Zach Barr of Scapi Magazine, detailed an unsuccessful attempt to track her down for an interview, including a trip to the old storefront that once served as a gallery for a protest show of surrealist art.

Rosemont’s family reached out to Scapi about the article, expressing interest in preserving her legacy with a legitimate interview. Barr agreed, and on September 11, 2018, writer and surrealist sat down to talk.

・・・

Can you speak to your initial interest in revolutionary causes, and how that led to a Chicago band of surrealists?

Rosemont: I was very interested in politics and anti-war activity, and I had heard it was very active at Roosevelt University. I signed up for a class called Social Disorganization, in the hopes that they were gonna tell us how to do it. I was looking for the class, and there was just about one person in the cafeteria. I said, “you wouldn’t know where this class is, would you?” It happened to be Franklin Rosemont. He had met Leonora Carrington, and had been mentioned to [famed French surrealist André] Breton in a letter by a friend of Breton’s. So he was already in touch with the surrealist group.

When I look back, I realize the 50s and the 60s were, in many ways, the top of the world for people. But there wasn’t a place for young people––you’d get out of school and couldn’t necessarily get a job. So that left a lot of people with nothing to do except think about changing the world. Which was actually not a bad idea.

Franklin Rosemont, Paul Guerin and Beth Guerin, John Simmons, several of our other friends got jobs at Barbara’s Bookstore. Barbara was a very interesting person. She said, “you young people know books, just order them. Order whatever you want.” So they ordered all sorts of great books––French surrealist books which sold amazingly, books on civil rights. It really was the best bookstore in Chicago, for a long time.

And “The Seed,” of course, was the underground newspaper and it was sold at Barbara’s. The police came and shut Barbara’s down, and a couple other places for selling “The Seed,” which they called “obscene.” But Barbara knew civil rights attorney Elmer Gertz. As part of his work in Civil Rights and Freedom of the Press, he got her off. It did change a lot of the censorship laws in Illinois, for better and for worse.

You mentioned that Franklin was already known, at least by letter, in France. Was that how your trip to France in 1965 to meet André Breton came about?

Rosemont: That was…sort of how it came about. We basically could read French, but we couldn’t speak it, so we were very anxious about going to France. But, we thought, we’d go to London and visit Freedom Press, an anarchist publisher there.

When we got to London, they weren’t very happy with us. We were too young. They didn’t like our clothes. Franklin, almost as a joke, said he was a musician, and that was the last straw. The customs official said, “we have quite enough of our own musicians, thank you very much.” He was going to send us back to New York, but, for better or for worse, we had only bought a one-way ticket. So they said, “Oh my God, we’ll have to send them back to New York on our own expense.”

I got up the next morning––they had us in detention with a bunch of people from Pakistan––and negotiated that they would deport us to Paris. There was a giant black X on our passport: “Deported From England.” The French officials never even looked at it. So there we were, in Paris, totally unprepared for anything.

In the area we were, all of the bookstores had Breton’s Surrealism And Painting in the window. It had just been reprinted. They also had a big poster, Le Carre Absolute, for a surrealist exhibition going on at that very time, about three blocks from our hotel. We went, and asked the owner of the gallery if Robert Benayoun had come in, because he had corresponded with us quite a bit. And the gallery owner said, “He’ll be here tomorrow!” So we met him, and then he invited us to his Surrealist New Year’s Eve party, which was something else.

But we really did not meet Breton until later in January and February. He was not in great shape, and he did not like to come out in the winter. I was really thrilled, because I realized that he’d been the inspiration for so much, when you think about what a small group can do. Because first, it was the Dadaists in Zurich, and then the initiative moved over to Paris after the war, and really it started with a few young men and… it didn’t really ever get to be a gigantic movement; it was just an influential one. I was very impressed by that. Of course, my French was still terrible, but after six months there, I could speak in French. I could dream in French.

But then, we went home.

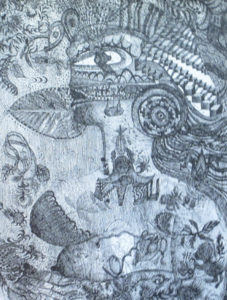

How did you make the shift from creating surrealist paintings and sculpture towards a focus in writing and theory?

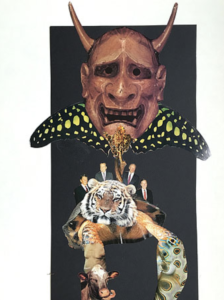

Rosemont: There weren’t as many galleries as there are now in Chicago. There was one, the Richard Feigen Gallery. Franklin went in and showed the woman there his collages, and she said, “Yes, we would love to give you a show. Come back next week.”

But then… I don’t know what happened. Maybe we left our magazine or something, but when we came back, she said, “Oh, we could never have a show of your stuff, because your politics are too far out.”

But the funny thing was, Richard Feigen himself was in New York, living it up with the Black Panthers. Who knows? He probably forgot to tell the Chicago people that radicalism was chic.

But in any case, he didn’t get the show at the Richard Feigen Gallery, which was about the only one that really seemed possible. We weren’t School of the Art Institute (SAIC) students, and, you know, the Institute does promote its own people. I love [surrealist art collective] “The Hairy Who,” but one of the reasons they’re successful is because they all went to the SAIC. So we moved over into writing.

We had had a terrible time trying to get the book of poems “The Morning Of A Machine Gun” published. In fact, that’s how I ended up at Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), because there wasn’t a printer in the world who would publish something called “The Morning Of A Machine Gun”—even if it was poetry. But SDS had a print shop. I kept going in asking, “When are you going to print it?” But they were too busy. So finally, I started volunteering in the print shop and eventually, I was on the national staff.

When we wanted to publish Arsenal [a journal of surrealist art and writing], a friend of ours lived in Hyde Park and was a printer. He went into his job, in the middle of the night, on a weekend, and printed it for us, free of charge. If you’re trying to do something decent, often you’ll get a lot of help with it. He was much older, he was an anti-war activist, he liked surrealism. So he did it.

Much of the original art that went into the publications, as well as the sculptures from Club Bugs Bunny, has been lost over time. What is the best way of preserving a history of surrealism and the art that was created, in the absence of the genuine artifacts?

Rosemont: We have a lot of the genuine stuff. And I have no idea what to do with it. I’m trying to get in touch with the Smart [Museum of Art] down in Hyde Park. They’re talking about the fact that they’d like to collect Chicago art. Well, I’ve got Chicago Art, and they can have it.

The other thing I encountered was a woman named Ilene [Susan Fort]; she did a wonderful book called In Wonderland, which was about surrealist women in art. She did a show in Los Angeles [at LACMA], so now she could conceivably help me find a place for it.

One of the problems now is, if it doesn’t exist somewhere in an institution, in a library, in an archive, where is it going to exist? I’m not going to start a museum of my own—although, back in the ‘70s or ‘80s, we wanted to buy a building and start a place called the Institute of the Imaginary Arts and Sciences. But we could never find a building cheap enough.

Some of it is online. I was just looking over my Wikipedia article and I nearly fainted, I started revising it right away. It’s so wrong.

The trouble is, none of us as artists have made a big name. It’s a thankless task, being an artist. You have to do it because you love it. So anyway, I don’t know. I would like to find a happy home for it.

In a 2012 interview with Never The Same, you said: “Surrealism at this point is almost a hundred years old, and I don’t know how much longer it’s going to go on as surrealism.” Do you have an idea of what comes after surrealism?

Rosemont: Surrealism itself, the philosophy and the structure of it, is pretty protean. It’s built to be adaptable. But people get tired of seeing the name in advertising. In some ways, I think young anarchists are very interested in surrealism; they’ll pick out some weird anarchist name and call it whatever they want. But it’s one of those ideas, and their methods, once they’ve been sort of let loose in society, it’s very, very hard to say that it won’t happen again.

One of the things that was important for me about surrealism was the group life. That we met once a week at least––Breton’s group met six or seven days a week, but they all lived close by. The group life is very important for surrealists. You don’t have ordinary friends, you have friends that are surrealist.

Living up here in Evanston, I’ve made some ordinary friends, but occasionally, I almost die of boredom. Because they talk about cooking, they talk about plants, they talk about house repair and taxes and their grandchildren. They don’t want to talk about politics, because that might be controversial. They don’t want to talk about changing society.

I’m in touch with people who are still calling themselves “surrealists”––in Spain, in South America, in Sweden, in England, in Germany––and they’re mostly older people. So I’m not sure where the younger people are. When I went to the anarchist conventions, many people gave me little booklets they put together that were quite nice, of writings and drawings. So I hope they’re still at it.

Surrealism, by nature, is always a response to politics, a way to open the mind of a vision of a new society. We’re currently in a period of political unrest and social upheaval that has drawn many comparisons to 1968. What role could, or does, surrealism continue to have for us today?

Rosemont: There’s still some of us who are politically engaged. We still put out flyers now and then. In many ways, we’ve pursued our own interests and hoped that they will change a point of view and the way people see and appreciate things. So we hope we’re continuing to do our work in a somewhat more remote way. We’re not out there in the streets, but hey, we’re too old.

We hate the government; it’s worse than ever. We’re kind of hoping that young people actually go out and vote in the midterm elections, but as you know, the electoral process is far from perfect; we’ve always been critics of it. It’s always manipulated terribly. Then, when the politicians get in, they do what they want anyway, so you lose either way.

I urgently worry about this country, but I would I not call for a violent revolution like I did in ‘68. Because I don’t think we could win. That’s the only reason. If I thought we could win, I’d be for it. No point in committing suicide, because we need the good people. You don’t want to risk too much, because change takes a long time. We should try every other avenue before we would go there. That would be the sensible thing to do.

In the time since the ‘68 surrealist exhibit at the Art Institute, the Institute itself has opened its new wing dedicated to modern and contemporary art, with a curator on their staff who specializes in the acquisition and the historical preservation of surrealist work. Do you believe that a surrealist exhibition is possible at the Art Institute? What would it take?

Rosemont: They opened the entire Museum of Contemporary Art because the Art Institute wouldn’t take Joseph Shapiro’s collection!

It’s true; occasionally, the Old Guard dies off, and somebody does something different, so it is possible that there’s somebody at the Art Institute who could mount a surrealist show that would fairly represent surrealism. But I still doubt that they would really be interested in involving it as a living movement.

“Now, surrealism ends in 1966.” Well, wait a minute, there’s still been surrealism going on since then. For some reason, there’s always that distance for academics and museums. I don’t know why they don’t try to stay more up to date.

When we were young people, no one took us seriously because they said, “they’ll be surrealists today, but tomorrow there’ll be something else.” I just don’t understand.

[The Museum of Contemporary Art] did put together a pretty nice surrealist exhibit, maybe two or three years ago [Surrealism: The Conjured Life from 2015]. They included a lot of people who use the surrealist method and created pretty nice work, but none of the surrealists had ever heard of them. Still, it was often a woman, or somebody who should have been included. So I actually liked the exhibit they put together.

But still. It’s not like the exhibitions Breton put together. They just don’t do that.

・・・

Penelope Rosemont is a writer and social activist, and a member of the original Chicago Surrealist Group from 1968. Her writings include Surrealist Women, Surrealist Experiences, and The Apple Of The Automatic Zebra’s Eye. She now lives in Evanston and contributes occasionally to surrealist journals.

Be First to Comment