photo by Rahul Pandit

When you upload a video to any platform, the site does something called compression to it to make it easier for website servers to handle. This usually results in slight degrees of quality loss, too small for most consumers to notice. A lot of creators do, and it’s actually become a trend on a lot of platforms to test these compression practices.

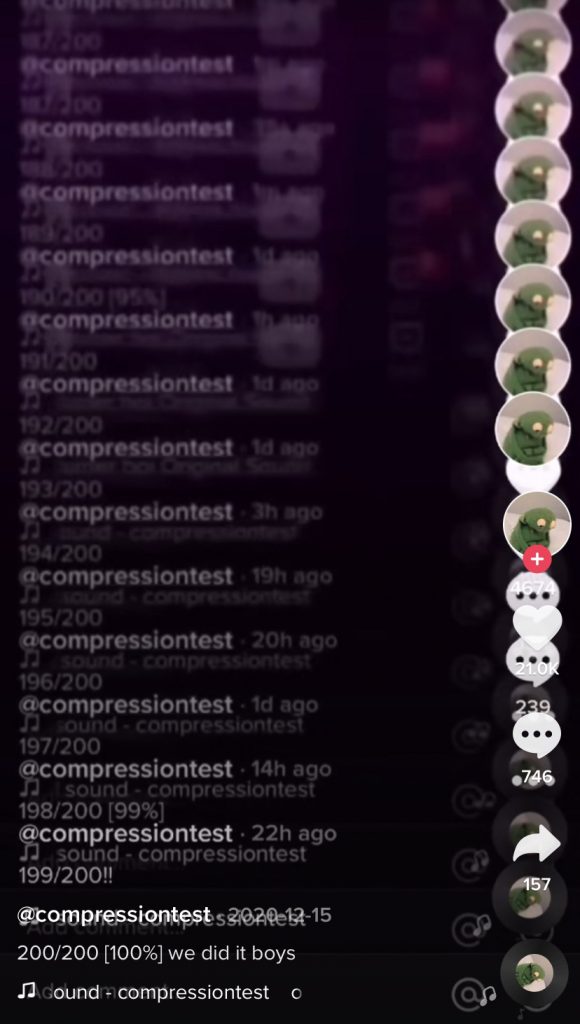

One Tiktok user, whose account is literally called @compressiontest takes this to the extreme. They set out with the goal to record the same video over and over again to see just how bad it can get.

“You’re not supposed to see this video. The compression on Tiktok videos when you screen record them is really bad. So I’m using this video as an experiment to screen record and repost the same video 200 times and seeing what the main one will look like.”

The account hasn’t posted since the experiment started, but original creator @jossh.mp3 intended from the beginning. It serves as a museum-like account, with its last post a garbled mess left to chronicle the results of the experiment.

To be frank, though, this is not the first time site compression has been studied. Popular tech youtuber Marques Brownlee made a video about this process back in 2019, citing especially evidence from the end equipment he favors.

“One of my favorite things about making videos with this high end gear, is the images that these cameras can capture is absolutely incredible,” Brownlee said. “Behind the scenes what you might not know is the actual video file that I’m uploading to youtube looks significantly better on my computer than on youtube.”

Brownlee also did some research on the history of youtube compression and found another 1000 times repeated compression test from 2010 by a channel called ontologist. This one’s recorded on a webcam, but it doesn’t take long for it to go the way of the others. By 1000 times you can barely make out the speakers shape and his voice is completely gone.

“What you will see and hear are the artifacts inherent in the video codec of both youtube and the .mp4 format I convert it to on my computer,” ontologist said in the video. “I regard this activity not so much as a demonstration of a digital fact, but more of as a way to eliminate all human qualities my speech and image might have.”

Brownlee hypothesizes that the decade difference in youtube and .mp4 codecs are influential in the results of this experiment. The entire video is fascinating, and he lays out the way that youtube compresses well as each pass happens.

Brownlee uploaded each and every pass to a separate youtube channel, that you can find here.

What is true, and Brownlee says this, is that compression algorithms have definitely changed over time. Not many other conclusions can be made, but more than anything, it’s a reminder that the work of video editors isn’t done after exporting and uploading, even if they’re not the ones doing it.

Be First to Comment