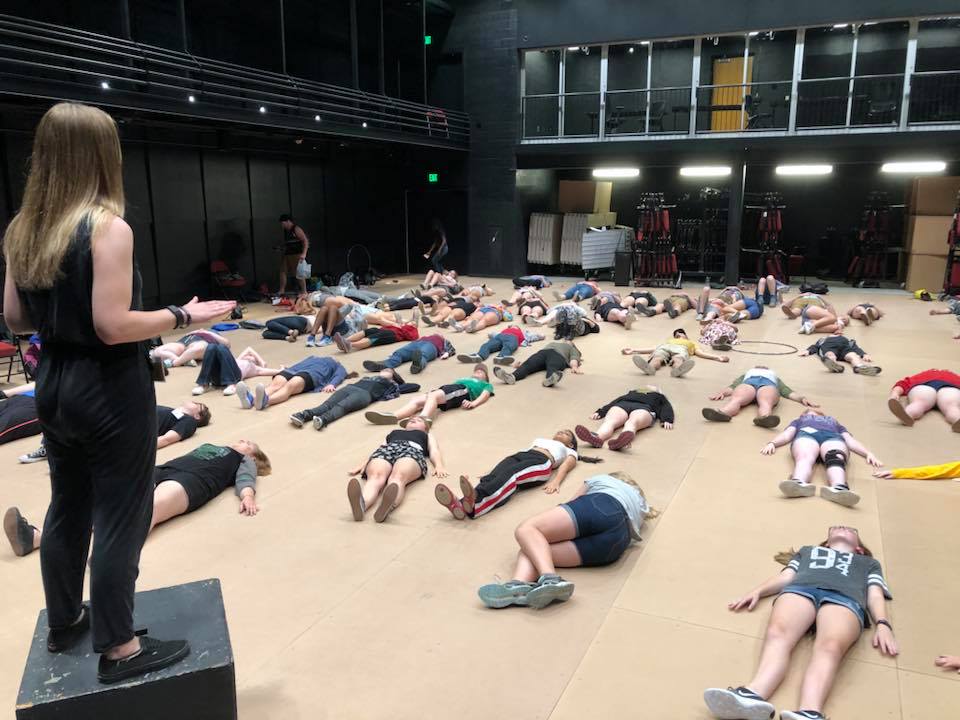

Pictured above: Ola Staszczynski teaches a theater group/Photo: Nathan Wyman

This is the fourth installment in a five-part series entitled “Building Consent Culture,” which defines and explores Consent Culture as a best practice to address the theater and performing arts industry. This series will feature artists of multiple disciplines dedicated to the advocacy of consent culture in Chicago’s DIY theater and performance art scenes.

CW: Sexualized Violence, Sexual Assault.

My name is Nick. My pronouns are they/them.

I’ve seen and experienced sexualized violence in my workplaces. I’ve been asked to compromise my bodily autonomy in the theater.

I’ve been asked to be an actor who always says: “Yes!”

I did not always understand the severity of what I experienced. I know that I am not alone. I’m calling for this to end.

#MeTooToThisEndsNow

As the national conversation regarding sexualized violence gains more recognition, Chicago’s theater community has had to face some of our most difficult and uncomfortable truths:

- Our theater has been a breeding ground for unsafe and unethical practices

- Our theater has valued “authenticity” over responsibility

- Our theater still exists in one of the most segregated areas in the country

- None of our progress will be of worth if our work is not intentional and intersectional

With all this in mind, the question remains:

How do we move forward?

The harsh reality is that this is not a new question. In the vast and rich history of theater, we have yet to make significant progress in creating and maintaining practices which advocate for the safety and well-being of performers. Therefore, we must continue to innovate and find new solutions. But how do we change the face of our culture?

We listen

If you are reading this and are a survivor of sexual assault, harassment, workplace violence and similar experiences, please know that we believe you, we support you, that this is not your fault and that you are not alone. Please also know that this is not contingent on whether or not you’ve elected to disclose your experiences to anyone. If you have, that took a lot of courage and power and that is noble. If you have not, you are just as valid and worth of care and support.

As a writer, I am someone who is paid to write my own personal values and beliefs. Consequently, it can make me feel that I have not done enough to listen to my peers and fellow survivors. Rather, I feel that I am working from my own points of view. At the core of my belief system is that we must actively create space for each other. We must listen to each other. We can’t all be authorities on every subject. No single one of us can solve this, so let us find power in community.

This installment of the Intimacy Direction series has been designed to be an act of listening, not speaking.

For this reason, I have elected to allow the words of others to hold my focus, our focus. We must create space for each other to speak our truths and to honor each experience as valid, even if it is at dissonance with our own.

Please hear these courageous voices. Listen to survivors.

Their courageous voices: owning your own voice

On June 24, 2018, I was sexually assaulted in a bar during Chicago’s Pride Festival.

The assault occurred during my process of writing this series, specifically this installment. As you can imagine, it has made writing this both difficult, cathartic and challenging in the way that it required me to speak truth to my own experiences. But as fearless as it might seem to be self-identifying now, this has been an incredibly difficult experience for me. In many ways, I am searching for ways to heal.

For me, putting survivors at the center of this conversation has also meant negotiating my own experiences. I am a survivor of sexual assault. I can’t help but ask why, then, it is more difficult to listen to my own voice in this context.

I can’t pretend to be able to offer any meaningful advice on processing—all I can say is that for me, the act of listening also includes introspective listening; how are my own experiences informing my advocacy? In what ways am I producing behavior that is unhealthy for myself and subsequently, my community? What does my body tell me I need today?

Friends, I’d just encourage you to listen to your body. The body is so fucking resilient and so are you.

Their courageous voices: conversations with intimacy professionals at the forefront of this work

I also found it would be entirely necessary to put the pioneers of Intimacy Direction at the forefront of this conversation. In my work on this piece, I was connected with numerous professionals with varying degrees of experience with intimacy work. In sourcing the following interviews, I sought to find a better understanding of how each individual artist interpreted their work as an Intimacy Director and the way in which their work interacts with the greater artistic communities.

I interviewed Tonia Sina, co-founder of Intimacy Directors International, to learn more about the professional perspective of Intimacy Direction:

・・・

What makes Intimacy Direction a necessity in the theater?

Sina: That’s a really complicated question, but for me, it’s a no-brainer of what makes it a necessity in the theater. Just like the way we have fight directors choreographing fights to make it physically safer, Intimacy Direction is the kind of thing that needs to be choreographed, handled professionally, and discussed beforehand in order for it to actually be safe for everybody.

And I mean emotionally safe more than anything else. The problem with the way the industry has been working in the past is that without Intimacy Direction, it has been a free-for-all. Everyone has been trying to figure out how they handle intimacy without standard protocol or even a shared and discussed an approach that we all can follow. We need one that has been researched, codified and workshopped over the years and that has been backed up and peer reviewed. It’s taking a stab at something that doesn’t really already have a method. That’s how many people have been getting in trouble with all these assault and harassment charges; people are having to taking it into their own hands without training.

How do actors play into the necessity of Intimacy Direction?

Sina: The majority of these cases have been people who don’t realize what it’s like to be a victim, and have taken advantage of their authority. So, a lot of what Intimacy Direction is about is giving a voice to actors, giving them the ability to have basic human rights and to be able to say, “No, I don’t want to do it that way, but what if I could do it this way?” And just give them that space to feel free to say that without fear of judgment.

In the past, it’s been, “You’re an actor, do what I say. I don’t care what you think,” which is what has been causing this problem in the first place. In that mold, people—namely younger actors—are going to fall by the wayside. They’re just not going to be consulted, so they just have to do what they are told.

And it’s not a slave job; it’s a job. It’s a profession like any other and actors deserve to be safe. They get to have a workplace that doesn’t involve harassment and abuse. It’s just like everybody else. And that’s what this is really about.

It’s a necessity, in that keeping people safe is a necessity. Intimacy Direction is meant to keep actors safe while keeping everybody that is collaborating on the same page when it comes to choreographing moments of heightened emotional content.

What is an IDI director able to offer a production that a non-trained “Intimacy Director” could not?

Sina: IDI Intimacy Directors are all mental-health and first-aid certified. We all have extensive theatrical movement backgrounds. We do come from different areas. Some of us are fight directors. I began as a fight director and then decided to drop it completely to switch to Intimacy Direction.

While we all have different backgrounds, we all agree on the pillars. So, what you’re going to get from us is a collaborative experience. You’re going to get someone who really knows how to read the director and help them navigate the story while keeping the actors safest in the work.

We are highly trained movement choreographers, and we are also performers and teachers, so we can demonstrate and teach. We are able to recognize trauma signs when they arise to help prevent further mental anguish. And generally, if approached, we will help anybody who is having a crisis or any kind of emotional breakdown when we’re working on the project, whatever the reason.

We’re going to be there for them, we’re not going to leave them or just say, “Okay, why don’t you just leave the room and, you know, handle this yourself?” Our job is to keep everyone safe. We are the safety net in the room. We’re responsible for what’s going on while we’re in our rehearsal space. We’re also responsible for keeping it professional due to the topic. You’re not going to get somebody who is trying to take advantage of the situation with their authority. Our personal lives are personal and our professional lives are separate from the work. Sometimes we have to take breaks to promote self-care, and we all support each other as colleagues.

You’re also literally not going to get somebody who is going to try to have sex with anybody they are working with. While we’re on contract, we won’t abuse that trust. That’s part of our agreement. So we keep the bar extremely high for our Intimacy Directors and I couldn’t be happier with that bar right now.

Is it difficult to advance from being an Intimacy Director to an IDI Intimacy Director?

Sina: It takes a while to get that title. We mentor people directly and it takes a long time before they feel confident to actually apply. There are people who call themselves Intimacy Directors now who maybe took a workshop or two or are trying to give it a go. And they might learn as they go—without training—how difficult it really is. And if you’re in a situation and you don’t know how to handle it because you haven’t been trained to handle that situation, you could very easily be charged with harassment yourself.

So, every Intimacy Director with us understands the ramifications of this work; we understand fully that we have committed to being the person responsible during the choreography of these scenes and prep for performance. If something goes wrong, it is on us to help fix it. Not everyone is ready to take that responsibility seriously. So we find that’s very important as part of this work.

What would you explain to someone about the work who is new to Intimacy Direction?

Sina: I hear a lot of things about people who aren’t trained with us or anyone and have traumatized people in their rehearsals from trying to navigate this. We have then had some come to us saying, “This person did this workshop and it was really unsafe. I felt traumatized during the process.” Usually, it’s a person who took one workshop and then tried to teach this information. What we do in these workshops is get people extremely vulnerable for the purpose of finding intimate relations with other people. That’s not something I’d recommend for a younger choreographer—somebody who hasn’t really tried acting training from the perspective of a director. You’re holding people’s vulnerability in your hands. I don’t recommend it for everybody.

Despite the fact that the exercises we teach seem simple, they’re quite complex. It took over almost fifteen years to create this technique. We are reading people’s bodies the entire time, watching postures and micro-expressions, and giving them a way out if they need a way out. So, we’re never forcing anybody to do anything without their consent.

Can you elaborate on how consent is used in your process?

Sina: I can’t speak for any other Intimacy Directors. I don’t know if they’re using consent all the time, or if they know how to navigate fully enthusiastic consent (not just coercive consent) unless I see them work in person. That’s how we got into this problem in the first place without understanding or mentioning consent. Essentially, IDI Intimacy Directors offer a product that empowers the actors while keeping them safer.

How does Intimacy Direction coincide with the need for psychological professionals?

Sina: We are not therapists, we are not counselors and we are not trained to handle therapy with actors. In fact, all of us have resources we give actors, should they need to seek help outside of rehearsal. If somebody feels they’ve been assaulted and they need therapy or counseling, all of us immediately go into help mode, which is ushering them to resources to help them get past this trauma as best as we can. Sometimes people go through something on the outside of rehearsal and it gets brought up in rehearsal. Things like that can happen when you’re dabbling in emotions like this. So, we are all under the agreement that should something happen in which somebody needs to seek help, we can help them find those resources.

How do you respond to the criticism that it is not always economically feasible for theaters to afford to hire or train an Intimacy Director, especially economically underserved communities?

Sina: Just like any business, if you find value in something you will budget for it. If you find value in having a large number of costumes or if you find value in an elaborate set, then you are going to budget that thing. If you find keeping your actors safe is a priority, you will find the budget to pay for an Intimacy Director. And if you don’t find it as important, you won’t.

I get it that it’s expensive. I get that putting up shows and films is hugely expensive. There are also theater companies and film productions in this country who have plenty of money and could be setting a standard that this is something that needs to be handled and not just brushed over the way it has been. There have been a lot of things that have fallen through the cracks because of no protocol. The amount of trauma I’ve researched and experienced in theater and film has been staggering.

I think [Intimacy Direction] worth the money. I think that hiring one of us, or someone, to handle these things with consent is worth the money. I don’t think traumatizing anybody or sacrificing the art is worth any bottom line.

Do you believe expanding the number of trained Intimacy Directors will help?

Sina: We are trying to make this more mainstream so that there are Intimacy Directors of all levels. So if you can’t afford one of us, there might be a movement coach in the area that can Intimacy Direct for you. If they aren’t fully trained, then you’re going to get the quality that you pay for—just like with anything.

We are working on training people as quickly as we can to release them into the industry. My response to that question, “What do we do if we can’t afford it?” is always: “Okay, well do you want to pay for a lawsuit for sexual harassment, or do you think it’s important to traumatize your actors so that they’ll never want to work with you again?” That’s what is happening in the industry right now. Theater companies are going under directly because they don’t have the proper protocol. If you want to chance it and do risqué and edgy theater that has nudity or simulated sex without handling it with a protocol that is safe for everybody, then you’re going to have consequences that will be far more expensive than hiring an Intimacy Director for a few hours to help make sure that doesn’t happen. Just make sure you trust your choreographer to use consent without coercion.

In what ways do you see Intimacy Direction expanding accessibility for otherwise marginalized communities?

Sina: The movement behind Intimacy Direction is about being inclusive for everybody—it really is. It’s not just about gender. In the past, the arts (and most things in our world), have been dominated by a Caucasian male perspective. When anything is dominated by a singular community of people over the others, it tends to fall into the perspective of the people in charge who have authority. In this, the stories aren’t being told of people who are underprivileged. The movement behind Intimacy Direction is to get all of the people who have been underprivileged and to give them a voice; to say that you’re allowed to say when things aren’t okay. You’re allowed to say, “I feel uncomfortable, is it okay if we look at this differently? Can we spend more time on this?” When you have a space that allows people to express themselves that way, it only makes the work more inclusive and collaborative. That goes for men, women—everybody.

Speaking of men, how do you see male-identified performers participating in this movement?

Sina: If I were to create a movement about women having authority over men, or If I were to say only women, not men, could be intimacy directors then that would defeat the purpose of the entire movement. We need male role models in this movement. We need everyone to be taking responsibility for what’s happened in the past, and to admit things have not been handled properly. I know a lot of men in the industry who have admitted their past mistakes and want to make this a better, more inclusive place for everybody. Because when it’s more inclusive, everybody wins. The work wins. The work is more natural, the choreography can go deeper, and it can be more dangerous. If people feel safe, they will relax and explore creating better, more aesthetically pleasing work out of intimacy on stage. This is about improving the art form by giving a container instead of making it a free-for-all. I believe that in that process, under the right leaders, all marginalized communities can have an opportunity to have a voice.

White cis males need to have a voice as well in this discussion. If only women are talking, none of this matters. This isn’t about taking away rights from anybody. This is about making it more inclusive for everyone. Using authority to start a relationship can go very wrong for everyone involved; at the same time, everyone has the right to a private life. It’s important for everybody to understand what’s been going on in the industry from differing perspectives, and how it needs to change for us to be better.

Do you feel that owning your own intersectional identity has influenced your approaches to intimacy work?

Sina: As a disabled female, I can say there are a lot of things I’ve had to ask for, and if I didn’t, no one would have known I was disabled. So, I have to be able to speak those truths and that can only happen in a safe environment. Whereas before I was afraid to say I was disabled because I was afraid that it was going to cost me jobs, I don’t fear that anymore. I wouldn’t want anybody else to fear that—that they wouldn’t have an opportunity because of something they don’t have control over.

Where do you see the future of Intimacy Direction?

Sina: I see Intimacy Direction becoming the new norm, or the way we handle these things; the bare minimum. For example, we have a scene, and we don’t want to take advantage of anybody. So we’re going to talk about boundaries beforehand. We’re going to communicate with the actors. We’re going to ask them if they’re consenting throughout the processes. Instead of people literally being assaulted to get a shot on camera, that we can choreograph it to look far more real; that there’s some slight-of-hand and masking. There’s a lot of ways we can portray sex and intimacy that is safe and is comfortable for everybody. My largest hope is that we will stop enabling this abuse.

I hope that IDI can continue to be at the forefront of the movement, that we can add more Intimacy Directors to our organization, and that we can keep training people on how to do this work and how to keep people safe—how to be leaders in the movement.

And to give underprivileged people of all backgrounds more of a role in the performing arts. Those stories need to be told.

・・・

I am very grateful to Sina for offering her perspectives on intimacy work and its role in facilitating a movement in the arts that hold us accountable. Each professional’s insight provides a framework for each person—regardless of their experience with intimacy direction—to deconstruct their own relationship with consent and the arts.

Call for submissions

Taking on this project with Scapi Magazine has been of the highest honor. I’ve felt incredibly privileged to have worked quite intimately [pun intended] with a diverse group of survivors and professionals. Writing this series has been affirming, challenging and inspiring. Identifying as a survivor is difficult at times. I find that, in many ways, I am still searching for ways to put some type of closure on my own personal experiences. As a writer, I can’t help but identify parallels in the way in which I am searching for ways to finalize this series. In speaking these truths, I realize that closure isn’t always the answer. This work, like our healing, does not end here.

For this reason, I’d like to invite you all to join me in the curation of our final installment of the Consent Culture series.

By clicking here, you will be redirected to a Google form, which will be our vehicle to curate the voices of our readers.

The submissions we receive will be used in the creation of our final installment of this series, which will be a community healing project in the form of a multimedia art piece.

If you have additional questions about the submission process or Intimacy Direction series, please feel free to contact me personally at nbenz16@gmail.com for further questions.

Stay tuned for the final installment in the five-part series, To Heal.

Be First to Comment